Dental Care Survey, Medicaid Managed Care Members

- Document also available in Portable Document Format (PDF)

IPRO

Experts in Defining and Improving

The Quality of Health Care

New York State Department of Health

Office of Managed Care

February 2007

IPROCorporate Headquarters

Managed Care Department

1979 Marcus Avenue, First Floor

Lake Success, NY 11042-1002

516–326–7767 • 516–326–6177

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Background

Objectives

METHODOLOGY

Population

Survey

Data Analysis

Methodological Considerations

- Response Rate Analyses

- Descriptive Results of Enrollee Survey

- Comparisons of Age Groups on All Enrollee Survey Items

- Predictors of Responses to Selected Survey Items

- MCO Variation

- Comparisons of Vendor Utilization on Enrollee Survey Items

- Comparisons of MMC and FFS Medicaid Groups

- Other Analyses

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Number of Adult Eligible Members and Surveys Mailed per Health Plan

Table 2. Number of Child Eligible Members and Surveys Mailed per Health Plan

Table 3a. Surveys Collected by Age Group

Table 3b. Response Rates for each Demographic Group by Payor

Table 4a. Number of Respondents and Response Rates for MMC Plans

Table 4b. Number of Respondents and Response Rates for FFS Medicaid Plans

Table 5a. Comparisons of Respondents and Non–respondents for MMC Members

Table 5b. Comparisons of Respondents and Non–respondents for FFS Medicaid Members

Table 6. Background Characteristics

Table 7. Oral Health Status

Table 8. Dental Care Information

Table 9. Barriers/Facilitators to Care

Table 10. Access and Availability of Dental Care

Table 11. Satisfaction with Dental Care and Health Plan

Table 12. Comparison of Children and Adults

Table 13. Significant Associations with Logistic Regression

Table 14. MCO Variability

Table 15. Comparison of MMC versus FFS Medicaid among Adults

Table 16. Comparison of Whites and Other Races

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

The purpose of this survey project is to assess the dental care that New York State Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) provide to their Medicaid enrollees, identify barriers to accessing care, and assess the satisfaction of recipients regarding dental care. This study was targeted to both members who receive dental benefits through their health plan and members whose dental care is paid via FFS Medicaid.

Poor oral health can impact children´s overall health, growth, school attendance, and can lead to medical complications. Dental caries comprises the single most common chronic childhood disease in the United States, and dental care remains the most prevalent unmet health care need for children. Several barriers to dental care have been identified, including lack of dental coverage, lack of adequate transportation, and a shortage of dentists willing to treat low–income, Medicaid, or disabled individuals. Significant disparities in the incidence and severity of oral diseases exist by race, income, education, disability status, homelessness, and migrant families.

Findings of the 2004 NYSDOH Medicaid Managed Care (MMC) Dental Provider Access and Availability Survey indicated that 53% to 89% of dentists/sites made appointments within the standard of 24 hours for urgent care and 28 days for routine care. These findings suggest that providers have open appointments, but they do not inform the extent to which members are actually visiting dentists, which is better measured by QARR. QARR rates for the Annual Dental Visit measure in NYS are low, with rates of 38%, 44%, and 43% for measurement years 2003, 2004, and 2005, respectively.

Methodology

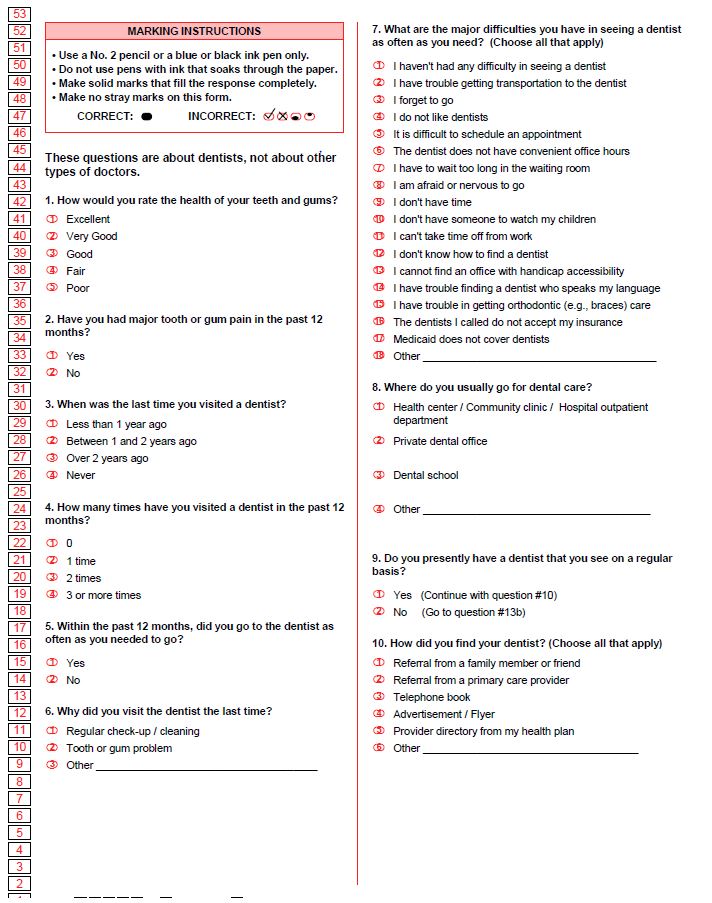

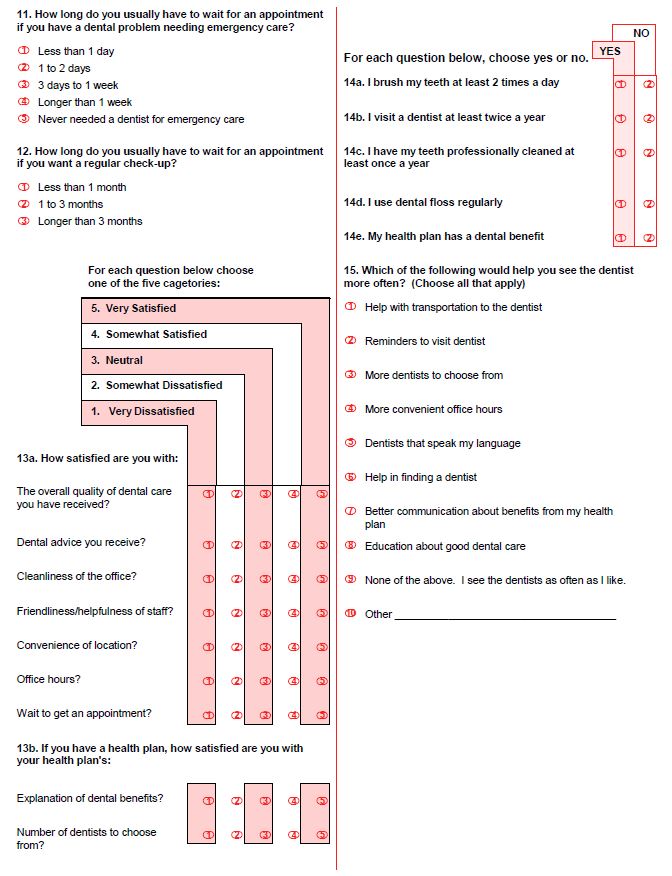

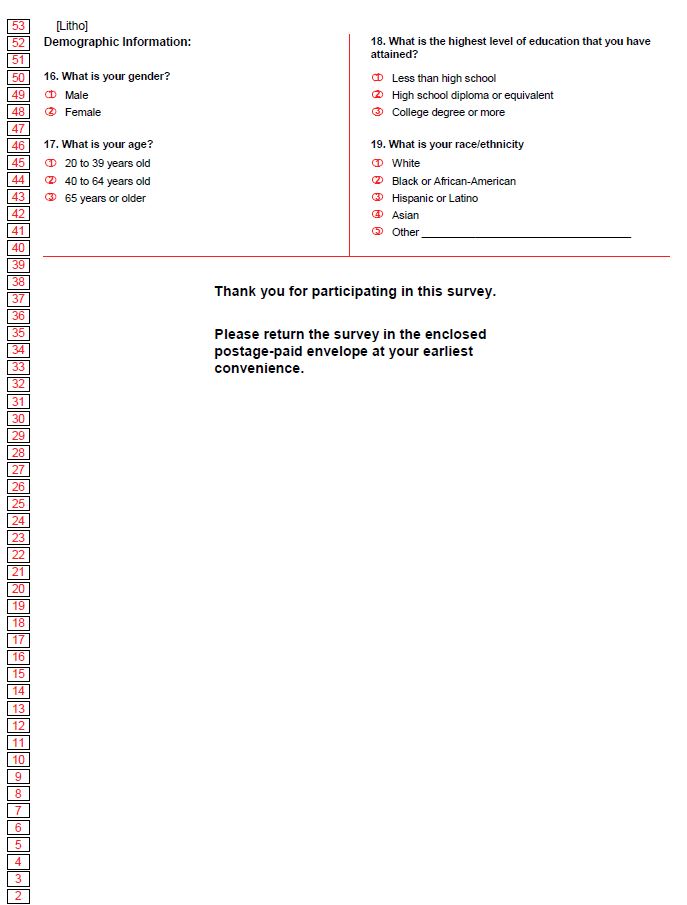

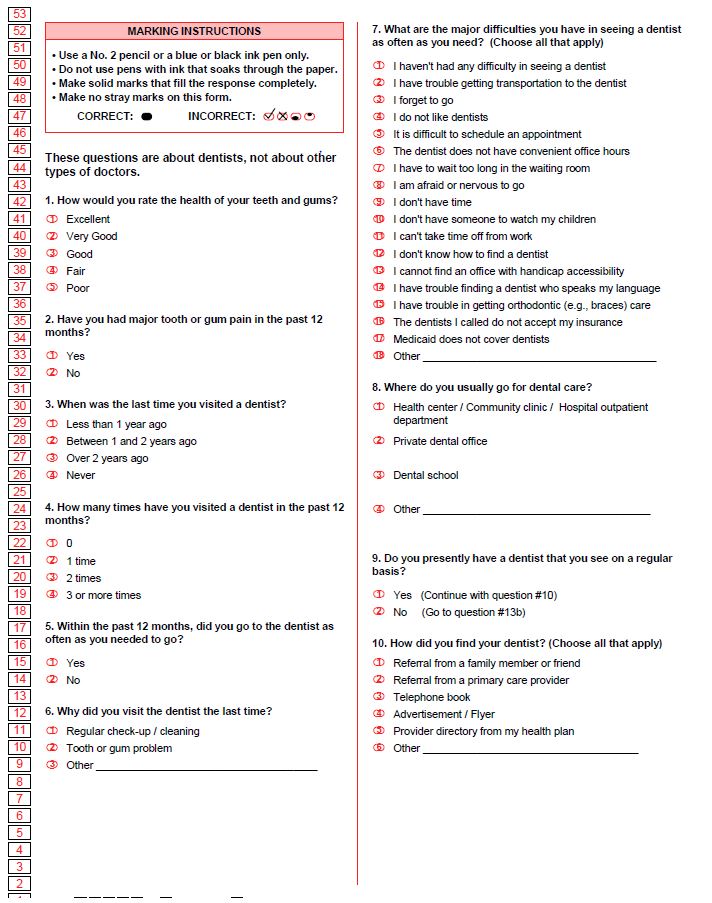

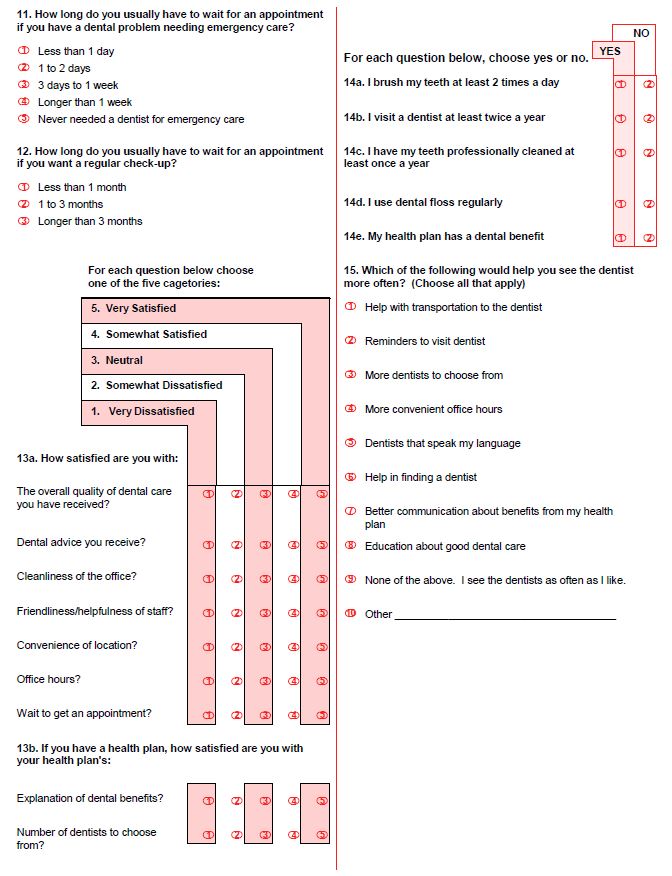

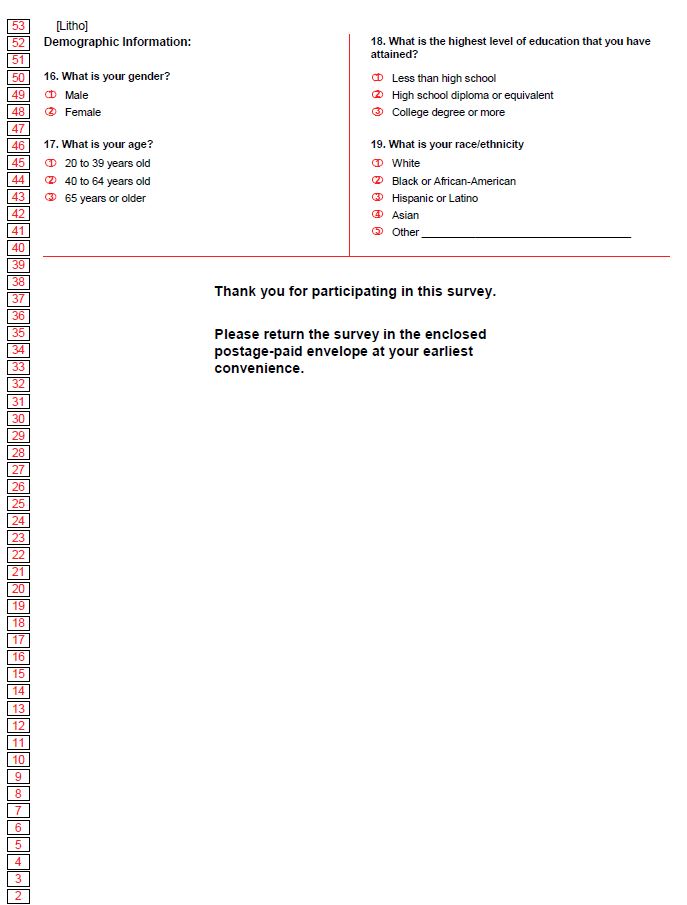

Three scannable mail surveys were constructed, one each for: adult members, parents/guardians of child members, and long–term care members (presented in a separate report). Key survey indicators included oral health status, dental care visit in the past 12 months, whether the member has a regular dentist, ability to make timely appointments, satisfaction with the dentist and the health plan, barriers and facilitators to receipt of care, and demographic characteristics.

The total number of surveys mailed was 9,600 surveys for the MMC group and 2,400 surveys for the FFS Medicaid group. The survey was distributed to members in March 2006 and re–sent to non–respondents in May 2006. Both English and Spanish versions were mailed to each member.

Results

Of the 12,000 surveys that were mailed, 1,553 (13%) were undeliverable, and 2,330 surveys were completed, yielding a response rate of 22.3%. The FFS response rate (26%) was higher than the MMC rate (22%). Response rates differed by health plan, ranging from 14% to 27% for the MMC cohort, and from 17% to 34% for the FFS cohort.

To determine the extent to which the survey findings are generalizable to the total population, members who completed the survey were compared with those who did not on demographic variables. Among both the MMC and FFS cohorts, members who completed the survey were older than members who did not. Among the MMC cohort, respondents were more likely to be female, white, SSI recipients, and NYC residents compared to non–respondents. Among the FFS cohort, respondents were more likely to be white and SSI recipients than were non–respondents.

Descriptive Results of Enrollee Survey

Age ranged from 18 to 65 among the 1,255 adult respondents, and from 4 to 17 among the 1,075 children. Among the combined age groups, 39% were male, 72% had at least a high school diploma, 33% were white, 33% black, 24% Hispanic, and 9% other. Oral health was reported to be excellent or very good by 32% of respondents, good by 34%, and fair or poor by 34%. One–third reported having tooth or gum pain in the past year.

The majority of members (64%) visited a dentist within the past year, while 47% reported going at least twice. Half said they went to the dentist as often as needed within the past year. The major reason they last visited the dentist was for a regular check–up or cleaning (58%), while 39% went for a tooth or gum problem. A total of 71% usually go to a private dental office for care, while 27% go to a health center, community clinic, or hospital outpatient department. Two–thirds reported that they have a dentist they see on a regular basis. Regarding dental care behaviors, 81% reported they brush their teeth at least twice a day, 55% visit a dentist at least twice a year, 61% have their teeth professionally cleaned at least once a year, and 40% floss regularly.

Overall, 62% reported at least one difficulty in seeing a dentist as often as needed. The most common barriers cited were afraid or nervous to go (15%), dentists called do not accept their insurance (14%), do not like dentists or their particular dentists (13%), it is difficult to schedule an appointment (12%), have to wait too long in the waiting room (11%), and have trouble getting transportation (9%). When asked what would help them see the dentist more often, 78% cited at least one facilitator. The most common were more dentists to choose from (32%), reminders to visit the dentist (31%), better communication about benefits from their health plan (24%), and more convenient office hours (18%).

Most members found their dentist based on their plan´s provider directory (45%) or a referral from a family member or friend (34%). When asked how long they usually have to wait for an appointment for a dental problem, 38% reported 3 days or longer. The usual wait for an appointment for a regular check–up was less than 1 month for 74% of the respondents, 1 to 3 months for 21%, and longer than 3 months for 5%.

Ratings of very or somewhat satisfied were 68% for wait to get an appointment, 74% for dental advice and for overall quality of care, 77% for office hours, 80% for convenience of location, 81% for friendliness/helpfulness of staff, and 82% for cleanliness of office. Satisfaction with health plans´ explanation of dental benefits was 56%, and satisfaction with the number of dentists to choose was 47%.

Comparisons of Age Groups on All Enrollee Survey Items

Children and adults were compared on each survey item. Children were more likely to be Hispanic, to have good oral health status, to receive appropriate dental care visits, and to be satisfied with dental advice and health plan´s explanation of benefits, and less likely to report barriers or facilitators to care than adults. No differences were found on the access and availability indicators.

Predictors of Responses to Selected Survey Items

Multivariate regressions were performed to identify predictors of dental visits in the past 12 months, problems with receipt of care, length of time to wait for a routine appointment, and satisfaction with care and with the number of dentists to choose from. Eight variables served as independent variables in each regression: age group, gender, race/ethnicity, education, NY region, whether have a regular dentist, usual place for dental care, and oral health status.

Members who have a regular dentist were more likely to report that they have visited a dentist in the past 12 months than were members who do not have a regular dentist.

Members who have a regular dentist and members who rated the health of their teeth/gums positively were more likely to say they have no difficulties than their counterparts. Members who were black, those who resided in NYC, and those whose usual place of care is at a private dental office were more likely to report that they receive a routine appointment within one month than their counterparts.

Members who rated their oral health positively were more likely to be satisfied with the overall quality of dental care received than those who rated their health negatively.

Members who were black, those with a regular dentist, and those who rated their oral health positively were more likely to be satisfied with the number of dentists to choose from than their counterparts.

MCO Variation

Variation among the 16 MMC plans was examined on each survey item. Items with the widest range in plan rates included race/ethnicity, whether usually receive dental care at a private office, and how members found their dentist. Moderate variation was found for how long members have to wait to get an appointment and for several satisfaction items, while oral health status and some dental care indicators varied less.

Comparisons of Vendor Utilization on Enrollee Survey Items

The 12 plans that used a dental vendor in 2005 were compared with the four plans that did not to assess differences on survey responses. Members from plans using a vendor were more likely to get care at a private dental office (75%) compared to members not using a vendor (64%). Those with a vendor were also more likely to have found a dentist via their provider directory and less likely to use a referral from a family or friend than those without a vendor.

Comparisons of MMC and FFS Medicaid Groups

The MMC cohort was more likely to be black and less likely to be white than the FFS cohort. Compared to the FFS cohort, the MMC cohort was more likely to report good oral health status, that they last visited a dentist less than a year ago, that they visited a dentist at least once in the past year, that they usually go to a private dentist office, and that they usually wait less than one month for a routine appointment. The FFS Medicaid cohort was more likely to report that they choose their dentist based on referrals from family or friends. No differences appeared on barriers/facilitators to dental care or satisfaction with care.

Racial Disparities in Barriers and Facilitators

Race was dichotomized as white or other, and the two groups were compared on each barrier to seeing a dentist and each facilitator. Compared to whites, other races were more likely to report that they forget to go and have trouble finding a dentist who speaks their language. Whites were more likely to report that the dentists they called do not accept their insurance. Similar results were revealed on facilitators to care. The other races were more likely to report that reminders to visit the dentist, dentists that speak their language, and education about good dental care would help them see the dentist, while whites were more likely to cite more dentists to choose from.

Differences between FFS Medicaid and MMC on Barriers and Facilitators

FFS Medicaid and MMC cohorts differed on only one barrier: FFS members were more likely to report transportation as a major difficulty in seeing the dentist. No differences appeared on facilitators.

Discussion

One in three respondents reported only fair or poor oral health and major problems in the past year. Oral health status was rated better for children than adults, but one in five children were reported to have had a major tooth or gum problem in the past year. Oral health status could potentially be improved with interventions that impact oral care behaviors and access to professional care. Self–care and regular professional visits and cleaning presents an opportunity for improvement. Education regarding the need for such preventive dental service can be helpful, but the barriers to accessing such care are likely multifactorial and require more than one intervention to achieve improvement.

The surveyed population reported higher annual visit rates than HEDIS rates; this could have been affected by response bias, since individuals who visited a dentist may have been more likely to complete the survey. Having a regular dentist was the single significant variable for increased likelihood of having visited a dentist in the past year and reporting no difficulties in seeing a dentist. Children had higher rates of dental visits than adults. Half of the respondents indicated that they did not see the dentist as often as needed, an unmet need more pronounced in adults. Attention to oral health by adult primary care providers, with education and referral, could potentially increase access to preventive dental services.

Reported barriers indicate the need for implementation of multiple strategies to affect improvement. A total of 62% of respondents reported difficulty in seeing a dentist as often as needed, including contacting non–participating dentists and fear of dentists. Individuals seeking care for urgent problems reported lower rates of timely access than those seeking routine care, which is consistent with more difficulty seeing a dentist reported by those with fair or poor oral health. Commonly cited facilitators to care included reminders, which could be generated by plans or primary care providers, and better communication about plan benefits; 16% were not aware that they had dental benefits. Educational interventions about plan benefits, how to access them, and locating participating providers could assist in decreasing barriers to care. Lack of coverage for needed services was cited often and may reflect a lack of education regarding benefits or unmet need.

A total of 74% of respondents reported receiving timely routine care appointments. Timely routine care was more likely among NYC respondents and those who obtain care in private offices, possibly related to numbers of participating providers or longer wait times in hospital or community clinics. More difficulty was reported for acute problems, with 38% waiting more than 2 days for acute care. Respondents´ perceptions of acute problems may not be comparable to the acute problems described in the Access and Availability survey, but there was considerable discrepancy between wait times for acute appointments in this study and the Access and Availability survey.

Waiting time for appointments, which could be even longer for those without a regular dentist who did not respond to this query, was the item with the highest rate of dissatisfaction. MMC members reported better rates of timely appointments for routine care than FFS members, but rates varied moderately among plans. Plans should evaluate their individual rates and assess possible plan specific barriers to timely care.

Low numbers and geographic maldistribution of participating providers treating Medicaid eligible individuals affect access to care. “More dentists to choose from” was the most commonly cited facilitator to care. Other barriers, such as difficulty scheduling and long wait times in waiting rooms, could be related to numbers of participating providers. Low reimbursement rates and administrative complexities have been cited as factors negatively impacting dental participation in Medicaid. Streamlining administrative processes could be beneficial in increasing provider participation.

Reported rates of satisfaction with overall care among respondents with a regular dentist were generally high. Satisfaction with health plans was lower, specifically for explanation of benefits and numbers of dentists to choose from. Educational initiatives about plan benefits offer opportunity for improvement; provider pool and availability should be further assessed.

MMC enrollees fared better for annual visits than FFS members, but variability among plans in several access and satisfaction areas presents opportunities for improvement. Plans should further assess specific rates for satisfaction, member access to provider information, and availability of participating providers. Efforts to encourage identification of a regular dentist, which is associated with increased annual dental visits and fewer difficulties seeing a dentist, could positively impact visit rates. Such efforts could include dissemination of plan provider and benefit information, and educational interventions regarding the need for regular dental visits.

The proportion of members by race/ethnicity varied widely by health plans. Black members were more likely to receive appointments within one month and to be satisfied with numbers of dentists. This could be related to particular plans´ characteristics.

Compared to whites, other races were more likely to report forgetting appointments and difficulty finding a dentist who speaks their language as barriers, and that reminders, education, and language appropriate dentists would facilitate care. Reaching culturally diverse populations can positively enhance utilization of dental services and should be part of improvement interventions. Whites were more likely to report that more dentists to choose from would facilitate care, which may be related to plan characteristics and/or geographic maldistribution.

The response rate of 22.3% was relatively low, particularly with the inclusion of English and Spanish surveys in each mail package. Although respondents differed from non– respondents on age, race/ethnicity, gender, NY region, and Medicaid aid type, the impact of the difference is most likely minimal, since there were large sample sizes, small demographic differences among the MMC cohort, and no differences noted in the comparison between the mail and telephone respondents. Furthermore, logistic regressions to determine the relationship of each demographic variable with each survey item yielded very few significant variables. Response bias is a potential limitation, in that members who responded were probably more likely to have visited a dentist than non–respondents, resulting in higher reported rates of care.

Recommendations

Educating Medicaid families on accessing the dental care system is necessary, as a lack of knowledge about available resources has impeded access to care. Plans could develop interventions to ensure that members are aware of dental benefits, covered services, and how to access benefits and participating providers, and ensure that culturally diverse populations are reached. Education regarding routine care could be considered for inclusion in primary care visits. Increasing the number of members with regular dentists could improve access to ongoing guidance; this could be facilitated by member education regarding benefits and available providers and primary care provider referrals.

Analysis of plan specific participating provider pools, as well as geographic distribution of providers, could be an area for future study. Streamlining administrative procedures such as care approval processes has been cited as an intervention to enhance provider participation as well as care; plans should evaluate existing administrative procedures if believed to be a factor in accessing care.

Reminders to visit the dentist, generated by plans or primary care providers, could be implemented to facilitate care. Further analysis of lack of coverage for needed services should be conducted to determine if there is true unmet need or lack of knowledge about covered services.

|top of section| |top of page|INTRODUCTION

This study assesses the dental care of members participating in New York State Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs). The primary purpose of this project is to provide the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) with information regarding the dental care that MCO enrollees receive, and to identify barriers to accessing care, and assess the satisfaction of Medicaid recipients regarding dental care. This study includes both members who receive dental benefits through their health plan and members whose dental care is directly paid via Medicaid, also referred to as FFS.

Background

Poor oral health can have a profound impact on children´s overall health, growth, school attendance, and social relationships, and can lead to medical complications. Dental caries comprise the single most common chronic childhood disease in the United States.1 Untreated tooth decay and the resulting pain and infection can cause eating, learning, and speech problems. Children with pain are more likely to be distracted at school and unable to concentrate on schoolwork. In adults, studies have found a correlation between severity of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and a mother´s chance of delivering a pre–term, low–birth–weight baby. Poor oral health can have a long–term impact on a person´s appearance, self–esteem, and ability to find work.2

While tooth decay is one of the most preventable childhood diseases, dental care remains the most prevalent unmet health care need for children. Several barriers to dental care have been identified in the literature, including lack of dental coverage, lack of adequate transportation, and a shortage of dentists willing to treat low–income, Medicaid, or disabled individuals.

Significant disparities in the incidence and severity of oral diseases exist by race, income, education, disability status, homelessness, and migrant families. Children from families with low income, children in minority groups (e.g., black, Hispanic, and Native American), children of parents with low educational attainment, and children with special health care needs are more likely to have untreated dental caries, greater levels of dental disease, and are less likely to have regular dental care than their counterparts3, 12

In addition to a lack of dentists willing to serve Medicaid recipients, many Medicaid families may place limited priority on obtaining dental care, which also leads to low utilization of dental services. Low–income families have many competing needs, are sometimes unaware of the importance of oral health care and may be unwilling or unable to wait for appointments or arrange transportation to a dental appointment.

Other factors contributing to the disparity in care may be limited knowledge about oral hygiene and difficulty accessing preventive dental care.

The twin disparities of poor oral health status and lack of dental care are most evident among low–income children. These disparities continue into adolescence and young adulthood, but to a lesser degree. Other population groups served by Medicaid, including low–income adults, pregnant women, and disabled adults are also at risk.

In reviewing the 2004 NYSDOH Medicaid Managed Care (MMC) Dental Provider Access and Availability Survey findings, Medicaid members appeared to have some difficulty in making appointments within reasonable time frames. The findings indicate that 53% to 89% of dentists/sites made appointments within the standard of 24 hours for urgent care and 28 days for routine care. Note that these findings suggest that providers have open appointments, but they do not inform the extent to which members are actually visiting dentists, which is better measured by QARR/HEDIS.

HEDIS/QARR rates for the Annual Dental Visit measure tend to vary across the state and are uniformly low. The HEDIS Annual Dental Visit measure assesses the percentage of enrolled members who had at least one dental visit during the measurement year. In 2004, rates for 4 to 21–year olds in New York ranged from 10.5% to 53.0%, with a median of 41.5%, among the 20 Medicaid/Family Health Plus (FHP) MCOs that provided dental benefits. In 2003, the overall plan rate in NYC was 37%, and in the rest of the state, it was 43%. Overall, QARR rates were 38%, 44%, and 43% for measurement years 2003, 2004, and 2005, respectively.

In an attempt to assess this discrepancy between the high rates of availability and the varying Annual Dental Visit rates and to explore barriers and facilitators of dental care, this study surveyed Medicaid managed care members to identify any potential barriers in accessing care and assess the satisfaction and knowledge of Medicaid recipients regarding the dental care they receive.

Objectives

This study assesses the dental care of enrollees participating in New York State Medicaid MCOs. The major objective of this project is to serve as a quality improvement study providing the NYSDOH with information to identify barriers and facilitators of dental care. The study evaluated, from the patient perspective, the dental care that MCO enrollees receive, identifying barriers in accessing care, and assessing the satisfaction of Medicaid recipients regarding dental care.

The specific objectives of this project are to determine:

- Whether enrollees receive dental care in a timely manner

- Whether enrollees are satisfied with their dental care

- Barriers and facilitators to receipt of dental care

- Differences in the above indicators among demographic groups

- Differences in the above indicators between plan enrollees with dental care benefits and members enrolled in plans in which dental benefits are carved out to FFS Medicaid

To achieve these objectives, a survey instrument was created to address several components of dental care. Three scannable mail surveys were constructed: one for adult members, one for parents/guardians of child members, and one for long–term care members (presented in a separate report). Both an English and Spanish version were mailed to each member. Key survey indicators included dental care visit in the past 12 months, ability to make timely appointments, satisfaction with the dentist, and barriers to receipt of care.

A similar survey was also conducted of MLTC members, which is presented in a separate report and includes the same analyses, whenever applicable, that are included in this report for adults and children.

|top of section| |top of page|METHODOLOGY

Members from health plans serving Medicaid recipients in New York State were asked to participate in the survey. This study included both members who receive dental benefits through their health plan and members whose dental benefits are not covered through their plan but are directly paid via Medicaid. In the remainder of the report, the former group will be referred to as the MMC cohort, and the latter group as the FFS cohort. In order to maximize recall ability, the study included members who met the most recent eligibility criteria, allowing for membership lag.

Population

Inclusion criteria for the study population are as follows:

- Medicaid managed care enrollees and FHP enrollees

- Ages 4 to 65

- Continuously enrolled in the year 2005, with no more than one gap in enrollment up to 45 days

- Enrolled as of December 31, 2005

The NYSDOH identified all eligible members based on the selection criteria and provided IPRO with demographic (e.g., date of birth, gender, address) data for these members. Across the adult and child groups in the NYS Medicaid program, 1,149,021 members met these criteria. There were 517,968 eligible adult members and 631,053 eligible child members.

Sampling was performed differently for the MMC and FFS Medicaid populations. Among the MMC cohort, IPRO randomly sampled 300 adults and 300 children from each of the 16 Medicaid health plans with a dental care benefit. Among the FFS cohort, IPRO randomly sampled 100 adults and 100 children from each of the 12 corresponding health plans. Note that for this study, five health plans that offer a dental benefit in some counties were excluded from the FFS population (i.e., CarePlus, Community Choice, Fidelis, GHI HMO Select, and United HC–NY). These five were included in the MMC sample. GHI PPO was also excluded because it only had 7 eligible members across all ages. Fewer cases were sampled for the FFS cohort than from the MMC cohort, since no plan comparisons were performed for the FFS population.

Based on the sampling algorithm, the total number of surveys mailed was 9,600 surveys for the MMC group (i.e., 600 x 16 plans) and 2,400 surveys for the FFS Medicaid group (i.e., 200 x 12 plans). As seen in Tables 1 and 2, a total of 1,200 adults for the FFS cohort, 1,200 children for the FFS cohort, 4,800 adults for the MMC cohort, and 4,800 children for the MMC cohort were mailed surveys. It was expected that this number of cases would yield a sufficient sample to permit plan–specific analyses for the MMC cohort, as well as analyses for the overall FFS results and MMC/FFS comparisons.

Table 1. Number of Adult Eligible Members and Surveys Mailed per Health Plan

| Plan Name | Total* | FFS Medicaid | MMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Sample | Total | Sample | ||

| AFFINITY HEALTH PLAN | 37,337 | 37,337 | 300 | ||

| AMERICHOICE | 30,910 | 30,910 | 300 | ||

| CAREPLUS | 17,652 | 38 | N/A | 17,614 | 300 |

| CDPHP | 7,863 | 7,863 | 100 | ||

| CENTERCARE | 19,534 | 19,534 | 100 | ||

| COMMUNITY CHOICE | 2,479 | 930 | N/A | 1,549 | 300 |

| COMMUNITY PREMIER PLUS | 19,163 | 19,163 | 100 | ||

| EXCELLUS | 15,497 | 15,497 | 100 | ||

| FIDELIS | 43,020 | 12,495 | N/A | 30,525 | 300 |

| GHI HMO SELECT | 1,035 | 154 | N/A | 881 | 300 |

| GHI PPO | 7 | 7 | N/A | ||

| HEALTHFIRST | 59,616 | 59,616 | 300 | ||

| HEALTHNOW | 8,944 | 8,944 | 100 | ||

| HEALTH PLUS | 48,848 | 48,848 | 300 | ||

| HIP | 64,948 | 64,948 | 300 | ||

| HUDSON HEALTH PLAN | 5,500 | 5,500 | 300 | ||

| INDEPENDENT HEALTH | 6,992 | 6,992 | 100 | ||

| MANAGED CARE HEALTH | 445 | 445 | 300 | ||

| METROPLUS | 45,373 | 45,373 | 100 | ||

| MVP | 395 | 395 | 300 | ||

| NEIGHBORHOOD | 17,950 | 17,950 | 300 | ||

| NY HOSPITAL CHP | 13,495 | 13,495 | 300 | ||

| PREFERRED CARE | 3,646 | 3,646 | 100 | ||

| ST BARNABAS | 6,379 | 6,379 | 300 | ||

| SUFFOLK | 2,372 | 2,372 | 100 | ||

| TOTAL CARE | 3,928 | 3,928 | 100 | ||

| UNITED | 20,352 | 18,541 | N/A | 1,811 | 300 |

| UNIVERA COMMUNITY HEALTH | 2,665 | 2,665 | 100 | ||

| WELLCARE | 11,623 | 11,623 | 100 | ||

| TOTAL | 517,968 | 179,765 | 1,200 | 338,203 | 4,800 |

*Total = sum of FFS + MMC populations

Table 2. Number of Child Eligible Members and Surveys Mailed per Health Plan

| Plan Name | Total* | FFS Medicaid | MMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Sample | Total | Sample | ||

| AFFINITY HEALTH PLAN | 42,966 | 42,966 | 300 | ||

| AMERICHOICE | 34,600 | 34,600 | 300 | ||

| CAREPLUS | 25,200 | 28 | N/A | 25,172 | 300 |

| CDPHP | 12,357 | 12,357 | 100 | ||

| CENTERCARE | 25,233 | 25,233 | 100 | ||

| COMMUNITY CHOICE | 3,818 | 1,379 | N/A | 2,439 | 300 |

| COMMUNITY PREMIER PLUS | 20,075 | 20,075 | 100 | ||

| EXCELLUS | 23,007 | 23,007 | 100 | ||

| FIDELIS | 62,360 | 18,261 | N/A | 44,099 | 300 |

| GHI HMO SELECT | 594 | 157 | N/A | 437 | 300 |

| HEALTHFIRST | 67,709 | 67,709 | 300 | ||

| HEALTHNOW | 11,272 | 11,272 | 100 | ||

| HEALTH PLUS | 62,328 | 62,328 | 300 | ||

| HIP | 60,322 | 60,322 | 300 | ||

| HUDSON HEALTH PLAN | 10,682 | 10,682 | 300 | ||

| INDEPENDENT HEALTH | 9,303 | 9,303 | 100 | ||

| MANAGED CARE HEALTH | 322 | 322 | 300 | ||

| METROPLUS | 56,079 | 56,079 | 100 | ||

| MVP | 861 | 861 | 300 | ||

| NEIGHBORHOOD | 25,079 | 25,079 | 300 | ||

| NY HOSPITAL CHP | 12,293 | 12,293 | 300 | ||

| PREFERRED CARE | 6,212 | 6,212 | 100 | ||

| ST BARNABAS | 7,553 | 7,553 | 300 | ||

| SUFFOLK | 3,440 | 3,440 | 100 | ||

| TOTAL CARE | 6,245 | 6,245 | 100 | ||

| UNITED | 23,045 | 20,457 | N/A | 2,588 | 300 |

| UNIVERA COMMUNITY HEALTH | 3,521 | 3,521 | 100 | ||

| WELLCARE | 14,577 | 14,577 | 100 | ||

| TOTAL | 631,053 | 231,603 | 1,200 | 399,450 | 4,800 |

*Total = sum of FFS + MMC populations

Survey

A scannable survey was developed based on other existing surveys in the literature and previous NYSDOH surveys; additional questions were crafted as necessary. To obtain a comprehensive evaluation of dental care, several areas were identified for survey.

The questions were framed to explore oral health status, whether the member has a regular dentist, number of times visited dentist in the past 12 months, reasons for not going to dentist, accessibility of the dentist, satisfaction with dental care and the health plan, and demographic characteristics. All questions were written to a fifth–grade reading level. Because response rates for non–disease specific surveys tend to be low for this population, the survey was limited in length to maximize response rates.

Survey items included several formats, as follows:

- Dichotomous items such as yes/no.

- Multiple choice questions, consisting of three or more exhaustive, mutually exclusive categories.

- Likert–type questions to measure the direction and intensity of attitudes.

- Open–ended questions to explore the qualitative, in–depth aspects of a particular issue.

- Demographic questions to classify characteristics such as gender and race/ethnicity.

Two similar surveys were developed: one for adults and one tailored for parents/guardians of children. Questions in the two surveys were the same except that items in the children´s version referred to the child.

IPRO conducted two focus groups in January 2006 to ensure that members would understand the content and that the questions were relevant to the population and the survey was comprehensive. One focus group was for the long–term care members and the other for adult members. The surveys were altered slightly as a result of the comments from the attendees of the focus groups.

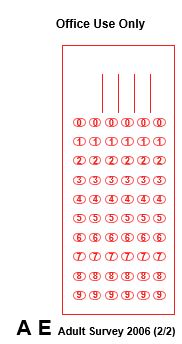

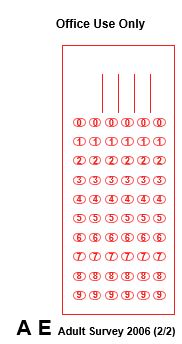

The survey was distributed to members in March 2006 and re–sent to non–respondents in May 2006 to maximize the response rate. Both English and Spanish versions were prepared and mailed in each package. Surveys were printed with randomly assigned identifiers used solely to track responses. Copies of the adult and child surveys are included in Attachments 1 and 2.

Participation in the survey was voluntary and confidential. Enrollees were told that it was optional to take part in the survey, that their answers would be kept strictly confidential, and that results would be reported in the aggregate. The survey included a sentence that directed them to call a toll–free number for assistance, if they needed it.

Data Analysis

Unless otherwise noted, all primary analyses were performed aggregating data for all enrollees, regardless of health plan. A focus of the analysis was to examine how enrollees receive dental care, and the perceived barriers to care. To explore whether care differs based on demographic characteristics, group comparisons were performed on selected key indicators for age group, gender, race/ethnicity, and other demographic characteristics. Analyses were also performed to explore plan rate variation. To test for any differences in proportions, chi–square analyses were employed for all comparative analyses.

The results section consists of 8 subsections. Specifically, the following areas of analyses were performed to address the objectives of this study:

- Response rate calculations of enrollee surveys, crosstabulations of response rates by age group; and response bias analyses (comparing respondents and non– respondents) on MCO, gender, age, race/ethnicity, and geographic region.

- Descriptive statistics on all survey items.

- Comparisons of age groups on all survey items.

- Predictors of responses to selected survey items.

- MCO variation on all survey items.

- Comparisons of vendor utilization on all survey items.

- Comparisons of MMC and FFS Medicaid on all survey items.

- Other analyses.

Sections A, B, and G included both the MMC and FFS Medicaid survey data. Sections C, D, E, F, and H only applied to the MMC respondents. MLTC survey data were reported in a separate document and will include the same analyses, whenever applicable, that are included in this report for adults and children.

Methodological Considerations

Because of the extensive number of indicators, many statistical tests were planned, thereby increasing the chance of a spurious statistically significant result. To limit the likelihood of reporting significance when it does not exist (type I error), the Bonferroni correction for multiple analyses was applied, resulting in an adjusted significance level of p<.001.

Due to the complexity of this survey, data manipulation was performed for analytical purposes. The following issues are discussed below:

- Items with multiple response options

- Skip patterns, with questionnaire items pertaining only to a subgroup of the sample

- Categorizing responses for crosstab analyses

Multiple Response Items

Three items on the survey asked the respondent to check all responses that apply, allowing the respondent to select multiple options. For such items, the total proportion of members selecting the corresponding options can sum to more than 100%. All proportions in this report are always based on the number of respondents, not the number of responses. For example, if 150 members answered a question with a total of 180 response options selected, the denominator was 150. These multiple response items are indicated in the tables with an "@" in the first column, and are listed below:

| Survey Item | |

|---|---|

| Q7 | Major difficulties had in seeing a dentist as often as needed |

| Q10 | How found dentist |

| Q15 | What would help see the dentist more often |

Items Pertaining Only to a Subgroup of the Sample

The survey contained one skip pattern, with some items based on a subset of the members who responded "Yes" to item 9. Items 10 through 13a were based on members who reported that they have a dentist to see on a regular basis. These items are denoted in the tables with a "◆".

Categorizing Responses for Crosstab Analyses

For statistical purposes, items that contained many response options were re–coded into fewer categories for all chi–square analyses. The descriptive results section (Section B), however, contains the raw frequencies of each item, and displays all options included in the survey. With the exception of questions 10 and 19, these items were dichotomized into two categories. The table below displays these items and the responses corresponding to each of the categories:

| Survey Item | Response Categories | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | Category 2 | ||

| 1 | Health of teeth/gums |

|

|

| 3 | Last time visited a dentist |

|

|

| 4 | Number of times visited a dentist in the past 12 months |

|

|

| 6 | Reason visited dentist last time |

|

|

| 7 | Major difficulties had in seeing a dentist as often as needed |

|

|

| 8 | Where usually go for dental care |

|

|

| 11 | How long usually have to wait for an appt. if have a dental problem |

|

|

| 12 | How long usually have to wait for an appt. if want a regular check–up |

|

|

| 13 | Satisfaction with dental care and health plan |

|

|

| 15 | What would help see the dentist more often |

|

|

| 18 | Education |

|

|

For item #19 (i.e., race/ethnicity), four categories were created (i.e., white, black, Hispanic, and other). The other race/ethnicity category included Asian, Native American, Arab, and Mixed Race. In the event that the respondent responded as Hispanic and any other race, the member was coded as Hispanic.

Note that, as is typical for survey research, whenever possible all "other" responses with open–ended text entered by the respondent, were re–coded to another existing response option that matched.

|top of section| |top of page|RESULTS

A. Response Rate Analyses

Table 3a displays the response rates, including the total number of surveys mailed and completed. Response rates were itemized by age group and by MMC/FFS sample.

Of the 12,000 surveys that were mailed, 1,553 (12.9%) were undeliverable, yielding an adjusted population of 10,447. The undeliverable rate is somewhat higher than other NYSDOH sponsored surveys of the Medicaid population, with undeliverable rates of 7.4%, 5.6%, and 7.6% in the Diabetes, Asthma, and ER Survey studies, respectively.

A total of 2,330 surveys were completed yielding an overall response rate of 22.3%. Among the completed surveys, 2,002 were in English and 328 were in Spanish. Across both age groups, the FFS response rate (25.7%) was higher than the MMC response rate (21.5%) at p<.001.

Table 3a. Surveys Collected by Age Group

| Children | Adults | |

|---|---|---|

| MMC | ||

| Surveys Mailed (Total Population) | 4,800 | 4,800 |

| Undeliverable | 529 | 627 |

| Adjusted Population | 4,271 | 4,173 |

| Completed Surveys | 864 | 952 |

| Response Rate | 20.20% | 22.80% |

| FFS Medicaid | ||

| Surveys Mailed (Total Population) | 1,200 | 1,200 |

| Undeliverable | 176 | 221 |

| Adjusted Population | 1,024 | 979 |

| Completed Surveys | 211 | 303 |

| Response Rate | 20.60% | 30.90% |

Response rates differed by health plan (see Tables 4a and 4b for MMC and FFS Medicaid, respectively), ranging from 13.9% to 26.8% for the MMC cohort, and from 17.1% to 34.3% for the FFS cohort.

Table 3b displays the response rates among the two payor groups (MMC and for FFS Medicaid) for each demographic group. Among the MMC cohort, females, SSI* recipients, and NYC residents were more likely to respond than their counterparts (i.e., males, SN or TANF recipients, and Rest of state residents, respectively). White and other race/ethnicities were more likely to respond than black members. Among the FFS Medicaid cohort, SSI recipients were more likely to respond than SN or TANF recipients. White members were more likely to respond than either black or other ethnicities.

Table 3b. Response Rates for each Demographic Group by Payor

| Field | MMC | FFS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (among adults) | |||||

| Male | 20.0% | 28.1% | |||

| Female | 24.1% | 32.0% | |||

| Aid Type (among adults) | |||||

| SSI | 27.9% | 38.6% | |||

| SN or TANF | 22.1% | 27.9% | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 23.5% | 30.0% | |||

| Black | 18.9% | 19.7% | |||

| Hispanic | 20.9% | 21.3% | |||

| Other | 22.7% | 23.5% | |||

| Region | |||||

| NYC | 22.9% | 24.8% | |||

| Rest of state | 20.3% | 26.0% | |||

_________________________

* Note: SSI = Supplemental Security Income, SN = Safety Net, TANF = Temporary Aid to Needy Families.

Table 4a. Number of Respondents and Response Rates for MMC Plans

| Plan Name | Adults | Children | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| AFFINITY | 43 | 17.5% | 26 | 10.4% | 69 | 13.9% |

| AMERICHOICE | 79 | 29.4% | 67 | 24.3% | 146 | 26.8% |

| CAREPLUS | 65 | 23.8% | 58 | 21.4% | 123 | 22.6% |

| COMMUNITY CHOICE | 69 | 27.1% | 46 | 17.5% | 115 | 22.2% |

| FIDELIS | 53 | 21.1% | 58 | 20.6% | 111 | 20.9% |

| GHI HMO | 62 | 23.3% | 35 | 13.8% | 97 | 18.7% |

| HEALTHFIRST | 43 | 17.5% | 53 | 19.6% | 96 | 18.6% |

| HEALTH PLUS | 61 | 22.2% | 57 | 20.7% | 118 | 21.4% |

| HIP | 61 | 23.7% | 58 | 21.6% | 119 | 22.6% |

| HUDSON HEALTH PLAN | 53 | 21.5% | 42 | 15.9% | 95 | 18.6% |

| MANAGED HEALTH | 52 | 19.5% | 49 | 18.5% | 101 | 19.0% |

| MVP | 53 | 22.4% | 52 | 21.5% | 105 | 21.9% |

| NEIGHBORHOOD | 71 | 24.9% | 56 | 20.1% | 127 | 22.6% |

| NY HOSPITAL | 76 | 27.8% | 51 | 19.2% | 127 | 23.6% |

| ST. BARNABAS | 58 | 21.4% | 77 | 28.2% | 135 | 24.8% |

| UNITED HC | 53 | 20.7% | 79 | 28.7% | 132 | 24.9% |

Table 4b. Number of Respondents and Response Rates for FFS Medicaid Plans

| Plan Name | Adults | Children | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| CDPHP | 24 | 30.0% | 22 | 26.5% | 46 | 28.2% |

| CENTERCARE | 28 | 29.8% | 8 | 8.4% | 36 | 19.0% |

| COMMUNITY PREMIER PLUS | 29 | 32.2% | 26 | 29.2% | 55 | 30.7% |

| EXCELLUS | 25 | 32.1% | 16 | 20.0% | 41 | 25.9% |

| HEALTH NOW | 33 | 37.9% | 26 | 30.6% | 59 | 34.3% |

| INDEPENDENT HEALTH | 25 | 32.9% | 15 | 17.0% | 40 | 24.4% |

| METROPLUS | 22 | 25.0% | 23 | 24.7% | 45 | 24.9% |

| PREFERRED CARE | 30 | 37.0% | 12 | 16.2% | 42 | 27.1% |

| SUFFOLK | 18 | 25.0% | 9 | 10.5% | 27 | 17.1% |

| TOTAL CARE | 28 | 36.4% | 21 | 26.3% | 49 | 31.2% |

| UNIVERA COMMUNITY HEALTH | 18 | 24.0% | 15 | 18.8% | 33 | 21.3% |

| WELLCARE | 23 | 28.4% | 18 | 19.8% | 41 | 23.8% |

Response Bias

To determine the extent to which the survey findings are generalizable to the total population, a comparison was conducted between members who completed the survey with those who did not on age, gender, race/ethnicity, aid type, MCO, and NY region. Data for the members were obtained from NYSDOH databases. This analysis excluded the undeliverable surveys. Table 5a displays the results for MMC and Table 5b displays the results for FFS Medicaid, with column percentages for both respondents and non– respondents. The comparisons of respondents with non–respondents were tested with chi–squares and those which are statistically significant at p < .05 are identified, since the number of comparisons are few.

Because the demographic data apply to the actual member, and the child survey respondent was the parent, analyses for gender and age were restricted to the adult survey sample. Also, because virtually all children had an aid type of TANF, analyses for aid type were restricted to adults.

Among the MMC cohort, members who completed the survey were older than members who did not complete the survey, with mean ages of 39.7 and 36.6, respectively (via t– test; p < .05). This pattern is typical of survey studies and coincides with other survey response bias results. Respondents were more likely to be female, be SSI recipients, and NYC residents. Regarding race/ethnicity, respondents were more likely to be white and less likely to be black compared to non–respondents.

Among the FFS Medicaid cohort, members who completed the survey were older than members who did not complete the survey, with mean ages of 42.9 and 38.8, respectively (via t–test; p < .001). Respondents were more likely to be white and be SSI recipients and less likely to be black compared to non–respondents. The two groups did not differ significantly on gender or region (NYC versus Rest of state).

Table 5a. Comparisons of Respondents and Non–respondents for MMC Members

| Field | Groups | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responded (n = 1,816) |

Did not Respond (n = 6,628) |

||

| Gender (among adults) | 0.004 | ||

| Male | 258 (27.1%) | 1030 (32.0%) | |

| Female | 694 (72.9%) | 2191 (68.0%) | |

| Aid Type (among adults) | 0.004 | ||

| SSI | 142 (15.0%) | 367 (11.4%) | |

| SN or TANF | 807 (85.0%) | 2841 (88.6%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.0001 | ||

| White | 708 (39.0%) | 2303 (34.7%) | |

| Black | 572 (31.5%) | 2448 (36.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 144 (7.9%) | 544 (8.2%) | |

| Other | 392 (21.6%) | 1333 (20.1%) | |

| Region | 0.003 | ||

| NYC | 897 (49.4%) | 3016 (45.5%) | |

| Rest of state | 919 (50.6%) | 3612 (54.5%) | |

| Age (among adults) | |||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 39.7 (13.0) | 36.6 (12.5) | 0.0001 |

Table 5b. Comparisons of Respondents and Non–respondents for FFS Medicaid Members

| Field | Groups | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responded (n = 1,816) |

Did not Respond (n = 6,628) |

||

| Gender (among adults) | n.s. | ||

| Male | 74 (24.4%) | 189 (28.0%) | |

| Female | 229 (75.6%) | 487 (72.0%) | |

| Aid Type (among adults) | 0.001 | ||

| SSI | 108 (35.6%) | 172 (25.5%) | |

| SN or TANF | 195 (64.4%) | 503 (74.5%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.0001 | ||

| White | 306 (59.5%) | 715 (48.0%) | |

| Black | 110 (21.4%) | 447 (30.0%) | |

| Hispanic | 19 (3.7%) | 70 (4.7%) | |

| Other | 79 (15.4%) | 257 (17.3%) | |

| Region | n.s. | ||

| NYC | 136 (26.5%) | 413 (27.7%) | |

| Rest of state | 378 (73.5%) | 1076 (72.3%) | |

| Age (among adults) | |||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 42.9 (12.2) | 38.8 (12.1) | 0.0001 |

Telephone Follow–up of Non–Respondents

A telephone interview was conducted among mail non–respondents to assess the extent to which the survey findings are generalizable to the total population. Telephone interviews consisted of a shortened form of the mail survey containing four representative questions drawn from the survey and three additional questions to ascertain why they failed to respond. Since the intent was not to yield complete surveys, the number of questions was limited to help increase the likelihood that phone respondents would participate. Interviewers telephoned a random sample of non– respondents shortly after the mail phase was concluded. The random sample of 1000 adult members was selected from the pool of non–respondents, after removing FFS Medicaid members, undeliverables, and members without a phone number. A sample was not selected for the child members.

Among the 1000 adult members who were called, 488 (49%) had either wrong phone numbers or non–working numbers, 276 could not be reached after 5 telephone attempts, 25 did not speak English or Spanish, 96 refused, 8 were on extended vacations, 3 passed away, and 1 was incarcerated. A total of 103 surveys were completed.

This analysis supplements the non–respondent analysis above. The phone respondents are not true non–respondents, and the comparison between mail and phone respondents´ tests for differences between members who agree to participate in the mail survey with members who agree to participate in the phone survey.

Items from the mail survey that were included in the phone survey:

- How rate health of teeth and gums (Q1)

- How many times visited a dentist in the past 12 months (Q4)

- Whether have a regular dentist (Q9)

- Level of satisfaction with the overall quality of dental care received (Q13a)

Three additional questions were asked inquiring (a) whether members recalled receiving the mail surveys, (b) if so, why they did not complete and send back their surveys, and (c) whether members have a preference of survey mode (see Attachment #3 for phone survey).

The telephone survey findings were compared to the mail survey on demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, race/ethnicity, aid type) as well as responses to the four common questions. The mail and telephone respondents did not differ significantly on any of the demographic characteristics or the survey item responses. Note that these results should be interpreted with caution due to the fact that a small number of telephone respondents participated, and thus may not be representative of the general population. Among the 103 phone respondents, 25 said they received the survey, and 78 said they did not. When asked which mode they would be more likely to complete a survey in, 52 said by phone, 28 said by mail, and 13 said either by email or on the web. It makes sense that the number choosing phone is high since they did not complete the mail survey but agreed to do the phone survey.

Only 21 respondents replied to the question as to why they did not complete and return the survey. Five of these stated they did not have time, five stated they did return the survey (although there was no record that they actually did), and two stated they did not understand the survey items.

B. Descriptive Results of Enrollee Survey

This section consists of the raw frequencies for all items in the survey, categorized by domain for ease of evaluating the results. All results were itemized based on type of survey (adult MMC, adult FFS, child MMC, and child FFS). Attachment 4 displays the results for each respondent category. Below, results focus on the MMC group, combining adults and children.

Background Characteristics of Respondents

Table 6 displays the responses to the items comprising the background characteristics of the members. Age was not a survey item but was provided by the NYSDOH. Among the 1,255 adult respondents, age ranged from 18 to 65, with a mean of 40 years old. Among the 1,075 children, age ranged from 4 to 17, with a mean of 13 years old.

Among the combined age groups in the MMC cohort, 39% were male. A total of 72% had at least a high school diploma. Of the respondents, 33% were white, 33% black, 24% Hispanic, and 9% other.

Table 6. Background Characteristics

| Survey Item | MMC n * 1,816 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| 16 | Gender (n = 1,719) | ||

| Male | 662 | 38.5 | |

| Female | 1057 | 61.5 | |

| 18 | Education (n = 1,667) | ||

| Less than H.S. | 463 | 27.8 | |

| High School | 844 | 50.6 | |

| College degree or more | 360 | 21.6 | |

| 19 | Race/ethnicity (n = 1,642) | ||

| White | 549 | 33.4 | |

| Black or African–American | 544 | 33.1 | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 397 | 24.2 | |

| Asian | 120 | 7.3 | |

| Native American (open–ended response) | 10 | 0.6 | |

| Arab (open–ended response) | 12 | 0.7 | |

| Mixed Race (open–ended response) | 10 | 0.6 | |

Oral Health Status

Responses to items pertaining to respondents´ dental health status are shown in Table 7. Regarding ratings of health of teeth and gums, members were almost equally distributed between favorable and unfavorable ratings. One–third reported that they had some major tooth or gum pain in the past 12 months.

Table 7. Oral Health Status

| Survey Item | MMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| 1 | Health of teeth/gums (n = 1,794) | ||

| Excellent | 199 | 11.1 | |

| Very good | 369 | 20.6 | |

| Good | 614 | 34.2 | |

| Fair | 406 | 22.6 | |

| Poor | 206 | 11.5 | |

| 2 | Had major tooth or gum pain in the past 12 months (n = 1,778) | ||

| Yes | 586 | 33.0 | |

| No | 1192 | 67.0 | |

Dental Care Information

The majority of members visited a dentist within the past year, while 47% reported going at least twice (see Table 8). Half of the respondents said they went to the dentist as often as needed within the past year. The major reason they last visited the dentist was for a regular check–up or cleaning (58%), while the remainder went for a tooth or gum problem, dentures, or braces. A total of 71% usually go to a private dental office for dental care, while 27% go to a health center, community clinic, or hospital outpatient department.

Two–thirds reported that they have a dentist that they see on a regular basis. Regarding dental care behaviors, 81% reported they brush their teeth at least twice a day, 55% visit a dentist at least twice a year, 61% have their teeth professionally cleaned at least once a year, and 40% floss regularly.

Table 8. Dental Care Information

| Survey Item | MMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| 3 | Last time visited a dentist (n = 1,799) | ||

| Less than 1 year ago | 1,143 | 63.5 | |

| Between 1 and 2 years ago | 340 | 18.9 | |

| Over 2 years ago | 238 | 13.2 | |

| Never | 78 | 4.3 | |

| 4 | Number of times visited a dentist in the past 12 months (n = 1,800) | ||

| 0 | 446 | 24.8 | |

| 1 time | 501 | 27.8 | |

| 2 times | 501 | 27.8 | |

| 3 or more times | 352 | 19.6 | |

| 5 | Whether went to the dentist as often as needed within the past 12 months (n = 1,785) | ||

| Yes | 900 | 50.4 | |

| No | 885 | 49.6 | |

| 6 | Reason visited dentist last time (n = 1,613) | ||

| Regular check–up / cleaning | 934 | 57.9 | |

| Tooth or gum problem | 627 | 38.9 | |

| Dentures (open–ended response) | 32 | 2.0 | |

| Braces (open–ended response) | 20 | 1.2 | |

| 8 | Where usually go for dental care (n = 1,664) | ||

| Health center / Community clinic / Hospital outpatient department | 442 | 26.6 | |

| Private dental office | 1180 | 70.9 | |

| Dental school | 18 | 1.1 | |

| Don´t go (open–ended response) | 24 | 1.4 | |

| 9 | Have a dentist to see on a regular basis (n = 1,730) | ||

| Yes | 1161 | 67.1 | |

| No | 569 | 32.9 | |

| 14a | Brush teeth at least 2 times a day (n = 1,739) | ||

| Yes | 1414 | 81.3 | |

| No | 325 | 18.7 | |

| 14b | Visit a dentist at least twice a year (n = 1,725) | ||

| Yes | 955 | 55.4 | |

| No | 770 | 44.6 | |

| 14c | Have teeth professionally cleaned at least once a year (n = 1,752) | ||

| Yes | 1061 | 60.6 | |

| No | 691 | 39.4 | |

| 14d | Use dental floss regularly (n = 1,716) | ||

| Yes | 685 | 39.9 | |

| No | 1031 | 60.1 | |

Barriers/Facilitators to Care

A total of 62% reported at least one difficulty in seeing a dentist as often as needed (see Table 9). The most common barriers cited were afraid or nervous to go (15%), dentists called do not accept their insurance (14%), do not like dentists or their particular dentists (13%), it is difficult to schedule an appointment (12%), have to wait too long in the waiting room (11%), and have trouble getting transportation (9%). Among the 95 open–ended responses, the most common difficulties cited were that Medicaid does not cover services they need, they do not have Medicaid, insurance, or a card, the office location is not convenient, and Medicaid dentists are not good. Most members reported that their health plan has a dental benefit (84%).

When asked what would help them see the dentist more often, 78% cited at least one facilitator. The most common were more dentists to choose from (32%), reminders to visit the dentist (31%), better communication about benefits from their health plan (24%), and more convenient office hours (18%). Among the 112 open–ended responses, the most common facilitators cited were that they want more specific dental benefits covered, closer location, and better dentists to choose from.

Table 9. Barriers/Facilitators to Care

| Survey Item | MMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| 7@ | Major difficulties had in seeing a dentist as often as needed (n = 1,680) | ||

| Have not had difficulty in seeing a dentist | 646 | 38.5 | |

| Afraid or nervous to go | 255 | 15.2 | |

| The dentists I called do not accept my insurance | 234 | 13.9 | |

| Do not like my dentist / dentists in general | 218 | 13.0 | |

| It is difficult to schedule an appt. | 196 | 11.7 | |

| Have to wait too long in the waiting room | 183 | 10.9 | |

| Have trouble getting transportation | 151 | 9.0 | |

| Forget to go | 133 | 7.9 | |

| Have trouble getting orthodontic care | 114 | 6.8 | |

| Dentist does not have convenient office hours | 99 | 5.9 | |

| Medicaid does not cover dentists | 88 | 5.2 | |

| Have trouble finding a dentist who speaks my language | 84 | 5.0 | |

| Don´t know how to find a dentist | 83 | 4.9 | |

| Can´t take time off from work | 76 | 4.5 | |

| Don´t have time | 74 | 4.4 | |

| Don´t have someone to watch children | 52 | 3.1 | |

| Cannot find office with handicap accessibility | 9 | 0.5 | |

| Other (open–ended responses): | 95 | 5.7 | |

| Medicaid does not cover services I need | 32 | ||

| Do not have Medicaid / insurance / card | 13 | ||

| Office location not convenient | 11 | ||

| Medicaid dentists are not good | 11 | ||

| Expense / out–of–pocket costs | 7 | ||

| Unclean office | 5 | ||

| Not enough choices of dentists in Medicaid | 5 | ||

| Other medical problems | 2 | ||

| Have no teeth | 1 | ||

| Other | 8 | ||

| 14e | My health plan has a dental benefit (n = 1,664) | ||

| Yes | 1391 | 83.6 | |

| No | 273 | 16.4 | |

| 15@ | What would help see the dentist more often (n = 1,669) | ||

| None. I see the dentists as often as I like. | 363 | 21.7 | |

| More dentists to choose from | 527 | 31.6 | |

| Reminders to visit dentist | 513 | 30.7 | |

| Better communication about benefits from my health plan | 405 | 24.3 | |

| More convenient office hours | 298 | 17.9 | |

| Education about good dental care | 256 | 15.3 | |

| Help with transportation to the dentist | 253 | 15.2 | |

| Dentists that speak my language | 248 | 14.9 | |

| Help in finding a dentist | 248 | 14.9 | |

| Other (open–ended responses): | 112 | 6.7 | |

| Want more specific dental benefits covered | 44 | ||

| Closer location | 15 | ||

| Better dentists to choose from | 14 | ||

| Help with anxiety | 11 | ||

| Faster appointment times | 8 | ||

| Better price | 5 | ||

| Equal treatment for Medicaid patients | 4 | ||

| Faster approval from Medicaid | 4 | ||

| Less waiting time at dental office | 2 | ||

| I have no teeth / have dentures | 2 | ||

| Handicap accessible | 1 | ||

| Other | 2 | ||

@ Multiple responses

Access and Availability of Dental Care

Three questions evaluated the ability of members to locate care and the ease of obtaining timely care (see Table 10). Each of these questions is based on members who have a regular dentist. Most members found their dentist based on the provider directory from their plan (45%) or a referral from a family member or friend (34%).

When asked how long they usually have to wait for an appointment if they have a dental problem, 29% stated they never needed a dentist for emergency care. After excluding those members who did not need a dentist, 35% reported they had to wait less than a day, 27% reported 1 to 2 days wait, 24% reported 3 days to 1 week, and 14% reported longer than 1 week. The usual wait for an appointment for a regular check–up was less than 1 month for 74% of the respondents, 1 to 3 months for 21%, and longer than 3 months for 5%.

Table 10. Access and Availability of Dental Care

| Survey Item | MMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| 10@ ◆ |

How found dentist (n = 1,114) | ||

| Provider directory from plan | 502 | 45.1 | |

| Referral from family / friend | 380 | 34.1 | |

| Referral from a PCP / doctor / nurse | 202 | 18.1 | |

| Telephone book | 47 | 4.2 | |

| Advertisement / Flyer | 39 | 3.5 | |

| Other (open–ended responses): In local neighborhood, walk–in Using long–term dentist Other |

35 24 8 3 |

3.1 | |

| 11 ◆ | How long usually have to wait for an appt. if have a dental problem (n = 1,140) | ||

| Less than 1 day | 281 | 24.6 | |

| 1 to 2 days | 222 | 19.5 | |

| 3 days to 1 week | 195 | 17.1 | |

| Longer than 1 week | 115 | 10.1 | |

| Never needed a dentist for emergency care EB | 327 | 28.7 | |

| 12 ◆ | How long usually have to wait for an appt. if want a regular check–up (n = 1,130) | ||

| Less than 1 month | 835 | 73.9 | |

| 1 to 3 months | 235 | 20.8 | |

| Longer than 3 months | 60 | 5.3 | |

@ Multiple responses

◆ Items based on skip pattern; rates based on respondents with a regular dentist.

⊕ Note: this response category is only presented here, and is excluded from other analyses.

Satisfaction with Dental Care and Health Plan

Among members who have a regular dentist, ratings of "very satisfied" ranged from 43% for wait to get an appointment to 63% for cleanliness of the office (see Table 11). Ratings of dissatisfaction (either somewhat or very) ranged from 9% for office cleanliness to 18% for wait to get an appointment.

Ratings of health plans were lower than ratings of dental care. Satisfaction with health plans´ explanation of dental benefits was distributed as 56% satisfied, 21% neutral, and 24% dissatisfied. Regarding the number of dentists to choose from, 47% were satisfied, 22% were neutral, and 31% were dissatisfied.

Table 11. Satisfaction with Dental Care and Health Plan

| Survey Item | MMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| 13a ◆ |

Satisfaction with overall quality of dental care received (n = 1,087) | ||

| Very satisfied | 541 | 49.8 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 266 | 24.5 | |

| Neutral | 158 | 14.5 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 60 | 5.5 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 62 | 5.7 | |

| 13a ◆ |

Satisfaction with dental advice received (n = 1,064) | ||

| Very satisfied | 522 | 49.1 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 268 | 25.2 | |

| Neutral | 151 | 14.2 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 66 | 6.2 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 57 | 5.4 | |

| 13a ◆ |

Satisfaction with cleanliness of the office (n = 1,083) | ||

| Very satisfied | 677 | 62.5 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 209 | 19.3 | |

| Neutral | 103 | 9.5 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 44 | 4.1 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 50 | 4.6 | |

| 13a ◆ |

Satisfaction with friendliness/helpfulness of staff (n = 1,099) | ||

| Very satisfied | 655 | 59.6 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 230 | 20.9 | |

| Neutral | 109 | 9.9 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 49 | 4.5 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 56 | 5.1 | |

| 13a ◆ |

Satisfaction with convenience of location (n = 1,069) | ||

| Very satisfied | 643 | 60.1 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 215 | 20.1 | |

| Neutral | 96 | 9.0 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 48 | 4.5 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 67 | 6.3 | |

| 13a ◆ |

Satisfaction with office hours (n = 1,054) | ||

| Very satisfied | 530 | 50.3 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 284 | 26.9 | |

| Neutral | 112 | 10.6 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 65 | 6.2 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 63 | 6.0 | |

| 13a ◆ |

Satisfaction with wait to get an appointment (n = 1,056) | ||

| Very satisfied | 455 | 43.1 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 268 | 25.4 | |

| Neutral | 139 | 13.2 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 102 | 9.7 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 92 | 8.7 | |

| 13b | Satisfaction with health plan´s explanation of dental benefits (n = 1,573) | ||

| Very satisfied | 520 | 33.1 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 355 | 22.6 | |

| Neutral | 325 | 20.7 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 162 | 10.3 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 211 | 13.4 | |

| 13b | Satisfaction with number of dentists to choose from (n = 1,507) | ||

| Very satisfied | 409 | 27.1 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 296 | 19.6 | |

| Neutral | 329 | 21.8 | |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 179 | 11.9 | |

| Very dissatisfied | 294 | 19.5 | |

◆ Items based on skip pattern; rates based on respondents with a regular dentist.

C. Comparisons of Age Groups on All Enrollee Survey Items

To assess whether differences exist between children and adults, group comparisons were performed on each of the survey items. Unlike the frequency distributions in Section B, items that contained many response options were re–coded into fewer categories for chi–square analyses. These analyses were limited to the MMC cohort.

Table 12 displays the results. Statistically significant differences emerged on race/ethnicity, oral health status, many of the dental care indicators, barriers and facilitators to care, and two of the nine satisfaction items. Children were more likely to be Hispanic than adults. Children were more likely to have good oral health status, to receive appropriate dental care visits, and to be satisfied with care, and less likely to report barriers or facilitators to care than adults. No differences were found on the access and availability indicators.

Table 12. Comparison of Children and Adults

| Survey Item | Adults n = 952 |

Children n = 864 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background Characteristics of Respondents | ||||

| 19 | Race/ethnicity | 0.0001 | ||

| White | 34.6% | 32.1% | ||

| Black or African–American | 36.7% | 29.1% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 20.3% | 28.6% | ||

| Other | 8.5% | 10.1% | ||

| Oral Health Status | ||||

| 1 | Health of teeth/gums is excellent, very good, or good | 53.5% | 79.5% | 0.0001 |

| 2 | Had major tooth or gum pain in the past 12 months | 44.0% | 21.0% | 0.0001 |

| Dental Care Information | ||||

| 3 | Visited a dentist < 1 year ago | 57.2% | 70.5% | 0.0001 |

| 4 | Visited a dentist 1+ times in the past 12 months | 70.9% | 80.0% | 0.0001 |

| 5 | Went to the dentist as often as needed within the past 12 months | 39.1% | 62.8% | 0.0001 |

| 6 | Visited dentist last time for regular check–up / cleaning | 42.6% | 74.6% | 0.0001 |

| 8 | Usually get dental care at private office | 74.2% | 69.5% | n.s. |

| 9 | Have a dentist to see on a regular basis | 59.0% | 76.0% | 0.0001 |

| 14a | Brush teeth at least 2 times a day | 83.3% | 79.2% | n.s. |

| 14b | Visit a dentist at least 2 times a year | 47.5% | 63.6% | 0.0001 |

| 14c | Have teeth professionally cleaned 1+ a year | 51.6% | 70.3% | 0.0001 |

| 14d | Use dental floss regularly | 45.6% | 33.9% | 0.0001 |

| Barriers/Facilitators to Care | ||||

| 7 | No major difficulties in seeing a dentist as often as needed | 30.8% | 47.0% | 0.0001 |

| 14e | My health plan has a dental benefit | 79.7% | 87.8% | 0.0001 |

| 15 | Nothing would help me see the dentist more often | 17.1% | 26.9% | 0.0001 |

| Access and Availability of Dental Care | ||||

| 10 @ ◆ |

How found dentist | |||

| Referral from family / friend | 36.8% | 31.8% | n.s. | |

| Referral from a PCP / doctor / nurse | 16.8% | 19.3% | n.s. | |

| Provider directory from plan | 41.6% | 48.1% | n.s. | |

| Other | 11.8% | 9.2% | n.s. | |

| 11 ◆ | Usually wait < 1 day for an appt. for dental problem | 32.7% | 36.3% | n.s. |

| 12 ◆ | Usually wait < 1 month for an appt. for regular check–up | 73.9% | 73.9% | n.s. |

| Very / Somewhat Satisfied with: | ||||

| 13a ◆ |

Overall quality of dental care received | 71.2% | 76.7% | n.s. |

| Dental advice received | 69.2% | 78.2% | 0.001 | |

| Cleanliness of the office | 81.4% | 82.1% | n.s. | |

| Friendliness/helpfulness of staff | 80.7% | 80.4% | n.s. | |

| Convenience of location | 83.0% | 78.1% | n.s. | |

| Office hours | 76.8% | 77.6% | n.s. | |

| Wait to get an appointment | 71.4% | 66.1% | n.s. | |

| 13b | Health plan´s explanation of dental benefits | 48.4% | 63.0% | 0.0001 |

| Number of dentists to choose from | 43.2% | 50.5% | n.s. | |

Note: Bold values represent the statistically higher value in that row.

@ Multiple responses

◆ Items based on skip pattern; rates based on respondents with a regular dentist.

D. Predictors of Responses to Selected Survey Items

Multivariate analyses were performed to identify predictors of dental visits, problems with receipt of care, and satisfaction with care. These analyses determined whether the group comparisons on the survey items are statistically significant after controlling for potentially confounding characteristics. This section was limited to the MMC cohort.

Five logistic regressions were performed, one for each dependent variable, across several domains:

Dental care information

- Whether visited a dentist in the past 12 months (Q4)

Barriers/Access

- Whether experienced difficulties in seeing a dentist as often as needed (Q7)

- Length of time to wait for an appointment for a regular check–up (Q12)

Satisfaction

- Whether satisfied with the overall quality of dental care received (Q13a)

- Whether satisfied with the number of dentists to choose from health plan (Q13b)

The following eight variables served as independent variables in each of the regressions:

- Age group (adult vs. child)

- Gender – item 16 (male vs. female)

- Race/ethnicity – item 19 (3 dummy variables: white vs. all others; black vs. all others; Hispanic vs. all others)

- Education – item 18 (less than high school vs. at least high school)

- NY region (NYC vs. Rest of state)

- Whether have a regular dentist – item 9 (yes vs. no)

- Usual place for dental care – item 8 (private office vs. clinic / outpatient department / dental school)

- Health status of teeth and gums – item 1 (excellent / very good / good vs. fair / poor)

For each of the dependent variables, Table 13 lists the variables with significant associations (with a p value of .001) via the multivariate regressions after controlling for potential confounding effects.

As can be seen, few significant relationships were detected, although each item was related to at least one of the eight predictors. The two most common significant predictors were whether the member has a regular dentist and the health of the member´s teeth and gums.

Dental care information

For "whether visited a dentist in the past 12 months", having a regular dentist was the only significant variable. Members who have a regular dentist were more likely to report that they have visited a dentist in the past 12 months than were members who do not have a regular dentist.

Barriers/Access

For "whether experienced difficulties in seeing a dentist as often as needed", two variables were significant. Members who have a regular dentist and members who rated the health of their teeth/gums positively were more likely to say they have no difficulties than their counterparts (i.e., members who do not have a regular dentist and members who rated their teeth/gums negatively, respectively). Conversely, members without a regular dentist and members who rated the health of their teeth/gums negatively were more likely to report at least one difficulty in seeing a dentist.

For "length of time to wait for an appointment for a regular check–up", three variables were significant. Members who were black, those who resided in NYC, and those whose usual place of care is at a private dental office were more likely to report that they receive an appointment within one month than their counterparts (i.e., members who were not black, those who resided outside of NYC, and those whose usual place of care is at a health center, community clinic, hospital outpatient department, or dental school, respectively).

Satisfaction

Only one variable was significantly related to "satisfaction with the overall quality of dental care received". Members who rated the health of their teeth/gums positively were more likely to be satisfied than those who rated the health negatively.

For "satisfaction with the number of dentists to choose from the health plan", three variables emerged as statistically significant. Members who were black, those with a regular dentist, and those who rated their teeth/gums positively were more likely to be satisfied than their counterparts (i.e., those who were not black, those without a regular dentist, and those who rated their teeth/gums negatively, respectively).

Table 13. Significant Associations with Logistic Regression

| Survey Item | N | Statistically Significant Variables (p < .001) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Whether visited a dentist in the past 12 months | 1368 | Have a Regular Dentist |

| 7 | Whether experienced difficulties in seeing a dentist as often as needed | 1295 | Have a Regular Dentist Health of Teeth/Gums |

| 12 ◆ | Length of time to wait for an appointment for a regular check–up | 955 | Race = Black NY Region Usual Place of Care |

| 13a ◆ | Satisfaction with the overall quality of dental care received | 918 | Health of Teeth/Gums |

| 13b | Satisfaction with number of dentists to choose from health plan | 1170 | Race = Black Have a Regular Dentist Health of Teeth/Gums |

◆ Items based on skip pattern; rates based on respondents with a regular dentist.

E. MCO Variation

To examine variation among plans on each of the survey items, the minimum rate, maximum rate, range, and median rate performance among plans are displayed for each survey item in Table 14. The analysis was based on the 16 MMC plans. Both children and adults were combined for the analysis. Across the 16 plans, the number of respondents ranged from 69 to 146, with a total of 1,816 respondents. The actual number of cases varied for each item, but each plan survey item rate comprised at least 30 respondents. Whereas all other analyses presented in this report are based on individual members, the analyses presented in Table 14 are based on individual plans, and thus, depict plan performance.