New York State Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Program

Consumer Educational Campaign Research Project

- Report is also available in Portable Document Format (PDF)

Final Report

September 2019

Center for Evaluation and Applied Research

The New York Academy of Medicine

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Methods

- Findings

- Field-testing survey findings

- Summary and Recommendations

I. Executive Summary

Introduction

The New York State Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) aims to fundamentally restructure the health care delivery system through an increase in community-level collaboration and more patient-centered practices and approaches to care. In order to ensure Medicaid beneficiaries and uninsured populations understand and engage with these changes, the New York State Department of Health (NYS DOH) contracted with The New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM) and the marketing firm Camino Public Relations (Camino), to conduct research that will inform a consumer campaign to help Medicaid beneficiaries proactively engage with these care enhancements.

Methods

A series of 25 focus groups were undertaken with Medicaid and uninsured consumers to elicit information on consumer experiences with health care, knowledge and perceptions of health care transformation, and recommendations on how best to disseminate and message health care information. Eighteen groups were conducted in English, two in Spanish, and one each in Russian, Korean, Mandarin, Bangla, and Haitian Creole. Camino used the information obtained from these groups to develop a set of health care messages that were field tested in a statewide survey assessing preferences regarding message wording and aesthetics. Below are the messages developed and field tested through this project:

- Message 1: Be your own advocate! It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally.

- Message 2: Be your own health champion! Even champions have the support of a team. Tell your healthcare team what matters to you so they can help you with physical and mental health needs.

- Message 3: Be your own health champion! It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally.

Findings

Focus groups:

- Participants connected their physical health to the social determinants of health and understood the importance of addressing both in the health care setting.

- Most participants did not have experience working with an expanded health care team (e.g., care coordinators and community health workers) but appreciated the potential benefit of these roles.

- Participants felt that the most impactful health messages are those that are shocking, intentionally fear inducing or very direct–and give detailed information about an action step people can take (e.g., provide a phone number to call).

- "Be your own advocate" was among the most common suggestions for the wording of a health care systems change educational campaign.

Message field-testing:

- Field testing survey respondents preferred "Be your own advocate" (40.6%) over "Be your own champion" (24.1%), though a quarter liked both phrases equally (25.9%).

- The preferred messages on both versions of the survey include the text, "It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally."

- Among the three messages tested, "Be your own health advocate" and the text immediately above (Message 1) appeared to communicate the messages´ intended ideas best.

- Most respondents reported higher likelihood to take action after seeing the message, "Be your own health advocate" (Message 1 above).

- When assessed alone, a blue background was the most popular choice for the campaign´s materials. Green was the most popular font color when assessed without a background. Black font on a blue background was the most commonly preferred combination of background and font colors.

Conclusions and recommendations

- Focus group participants and survey respondents preferred "Be your own health advocate" to "Be your own health champion."

- Participants preferred messages with the text: "It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally." This text also more effectively communicated the intended information. It is recommended that independent of tagline, the "It´s your health and your voice" text be used.

- Generally, people had a positive reaction to all messages and indicated that they would be likely to take action, including sharing the message or changing something about the way they use health care after seeing the messages.

- Focus group participants readily described health messaging campaigns that they felt were impactful, suggesting an educational campaign around health care could be influential.

II. Introduction

The New York State Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program was implemented to fundamentally restructure the health care delivery system by reinvesting in the Medicaid program with the goal of reducing avoidable hospital use by twenty-five percent over a five-year period. DSRIP promotes community-level collaborations and aims to transform the Medicaid program to a more patient-centered system.

As DSRIP is implemented, the target population, including Medicaid beneficiaries and the uninsured, must know how their system of care is changing. The New York State Department of Health (NYS DOH) contracted with The New York Academy of Medicine (NYAM) to conduct research for a consumer education campaign. The research included focus groups and the development and field testing of messages. These efforts will inform a consumer campaign to help educate Medicaid beneficiaries and the uninsured about transitions in health care, so they can better understand and appropriately respond to changes they observe and can proactively engage with care enhancements.

The DSRIP consumer education research project was implemented by NYAM´s Center for Evaluation and Applied Research (CEAR) with partner Camino PR over the course of 16months in 2018-2019. The project included focus groups and interviews with health care stakeholders, focus groups with Medicaid members and the uninsured across NYS, and surveys with NYS residents. The focus groups elicited information on consumer experiences with health care, knowledge of and perceptions of health care transformation, and recommendations on dissemination and messaging of health care information. Following the focus groups, NYAM worked with Camino, a full-service strategic communications agency, and the NYS DOH to develop and field test messages. NYAM then tested those messages through online and in person surveys with NYS residents. This report describes methods and findings from all components of the project.

|top of section| |top of page|III. Methods

This work is based primarily on two data collection activities: a series of focus groups with Medicaid and uninsured consumers and a field-testing survey with New York State residents.

Focus groups

Twenty-five focus groups were conducted with Medicaid beneficiaries and uninsured consumers (N=234) to elicit information that was used to develop and test messages for the DSRIP educational campaign. Eighteen groups were conducted in English, two in Spanish, and one each in Russian, Korean, Mandarin, Bangla, and Haitian Creole. These groups focused on consumer experiences with health care, knowledge and perceptions of health care transformation, and recommendations on how best to disseminate and message health care information. (see Appendix A and B for focus group guide and additional information regarding methods).

A total of 234 individuals participated in the consumer focus groups. Over half were female (61%). Twenty percent were Black or African American, 18% were Latino, and 44% were White. Seventy percent were on Medicaid and 11% were uninsured (see Table 2 in Appendix C).

Field-testing surveys

In the second stage of the project, Camino used the information obtained from the focus groups to develop a set of educational messages (see the section below). NYAM, in partnership with Camino and DOH, developed surveys to field test the messages with NYS residents. The survey (N=926) was designed to solicit input regarding (1) message content that most clearly communicates the intended information and (2) font and background colors that are most appealing and legible. (see Appendix D and E for survey instrument and additional information regarding methods). Messages and surveys were available in English, Spanish, Bangla, , Chinese, Korean, Russian, and Haitian Creole.

Most survey respondents were ages 26-45 (39.2%) or 46-65 (33.8%). The majority identified as women (69.4%). Approximately four in ten (42.4%) lived in NYC; approximately half lived in either Buffalo (26.3%) or Albany (23.8%). One in four were black or African American; Asian and Latinx participants made up 15% and 13% of the sample, respectively.

The majority of participants took the survey in English (n= 746, or 80.6%). The number of participants completing the survey in languages other than English were as follows: Spanish: 32; Bangla, Chinese, Korean, and Russian: 30, each; and Haitian Creole: 28. Participants most commonly indicated they had attended some college (30.5%) or were college graduates (37.9%). Just under half of participants said they were covered by Medicaid or were uninsured (47.7%). [See Appendix F for more detailed demographic information - including specific information about Medicaid and uninsured participants as well as those who speak languages other than English].

Message development

Using content from the consumer focus groups, Camino PR, in partnership with DOH and NYAM, developed messages for field testing. To develop the messages, Camino reviewed focus group transcripts and summary reports for concerns, needs, and recommendations that were common across groups. Camino focused on developing messages that sought to: 1) emphasize health care consumer autonomy; 2) focus on consumer options; and 3) expand the concept of health care to include nonmedical supports.

The messages developed for field testing are:

- Message 1: Be your own advocate! It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally.

- Message 2: Be your own health champion! Even champions have the support of a team. Tell your healthcare team what matters to you so they can help you with physical and mental health needs.

- Message 3: Be your own health champion! It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally.

See Appendix G for more details on message development.

|top of section| |top of page|IV. Findings

Focus group findings

The focus group findings described below highlight the data most relevant to the development and dissemination of successful health messaging, since that was the focus of the project.

These findings include an overview of participant perceptions and experiences with health and the health care system, as well as perspectives and recommendations related to effective health care messaging and dissemination strategies. These findings provided a foundation for the development of the final messages tested in the survey component of this project and are organized according to two main themes: (1) participant experiences and perspectives on health and health care and (2) health information and messaging.1

Experiences and perspectives on health and health care

Health and health behavior

- Focus group participants experienced a broad range of health conditions and health-related risk factors including HIV, chronic pain, overweight, mental illness, stress, drug dependence, diabetes, cancer, disabilities, and homelessness.

- Participants were conscious of the need for prevention and disease management and described multiple ways they tried to improve their health–as well as what motivated action.

- Participants experiences of ill health and use of health care informed their thinking about what was needed and what was appropriate with respect to an educational campaign.

“I recently lost 40 pounds. I had gone up to 260 pounds and that was after I had my son and then I had postpartum depression… I want to be alive for my children. So, it´s like one thing at a time. I haven´t given up smoking yet, but one thing at the time. (New York City)

Perspectives on social determinants of health

- Most participants appeared to recognize the link between social factors and health, though some reported they did not want their doctors to ask about non-medical issues and said they would be skeptical of providers´ intentions and use of the information if they did ask.

- Many doubted physician capacity to successfully address social problems.

I think it would be okay, but like if you´re asking me that question, then are you in a position to help me? Don´t just ask. Especially housing. That would kind of annoy me if they asked me a question that they have no power to do anything about. (Riverhead)

Perspectives on an expanded care team

- Most participants did not have experience with a care coordinator or community health worker, though they understood and appreciated the potential of these roles –particularly with respect to addressing the social determinants of health.

- Those who did have experience with care coordinators were primarily new mothers and individuals with complicated chronic conditions, such as HIV, diabetes, mental illness, or a substance use disorder.

The doctors are busy. The nurses are busy. But if there's somebody there that could actually connect all the dots together, it would make life a lot easier. (Poughkeepsie)

I´ve had a lot of health issues over the past year and [name of health plan] through Obamacare actually assigned me a social worker who called me out of the blue and was asking what could she help me with and this and that. I´m a diabetic, so she was helping me with getting the pump. It was really nice, because she did reach out and she was able to pull some resources and help me with things that I needed help with. (Riverhead)

Health information and messaging

Information sources and memorable campaigns

- Participants access health information from a wide variety of sources, including television, radio, billboards, friends and family, insurance companies, their doctors´ offices, and social media.

- The most impactful or memorable campaigns were those that were intentionally fear inducing or very direct.

- More positive messages were also described as memorable, particularly those reminding participants of their personal relationships or that encourage personal connection.

- Participants felt that messages most likely to motivate change are those that include an action step and provide specific detailed information, like a phone number to call.

The scare tactic ones would really work. You remember them a lot more, like texting and driving and the opioids. (Albany)

They should [give information] and ways to follow through. Like the New York State Smokers´ Quit Line. They give you a number. It´s like helpful. (Albany)

Recommended messages and messengers

- Participants suggested messages for the educational campaign, with "Be your own advocate" being the most frequently suggested. Others included (in no particular order):

- We listen.

- We´re here to help.

- A doctor is here to help, not hurt.

- The Health Department is worried about you.

- Your doctor, your friend.

- Care about yourself, care about others, and don't–if you have something

- communicable–obviously, don't share it.

- As citizens of New York, we´re entitled to this, we´re waiting for you to ask us. What are you waiting for?

- Here are all the steps you can take to stay healthy. Here are all the places you can contact.

- Health is not just physical.

- Healthy, wealthy, and wise.

- Health starts at home.

- Be your own doctor.

- Your health depends on you first.

- Help us help you.

“I think that would be a great common-sense thing to implement, to educate and advertise to the general public, that if you have needs like housing, food, abuse, or whatever – that there are resources. And in general, that these are some services that you can seek out that will affect your health. And so, in a way, that's also the being your own advocate for your life. (Poughkeepsie)

Health Champion vs. Health Advocate

In the final four2 consumer focus groups, facilitators asked participants for their preferences on two potential messaging campaign phrases: "Be your own advocate" and "Be your own health champion."

- In one group, participants reacted negatively to "Be your own," which was the start of both messages. They objected to the implication of individual responsibility for health issues, rather responsibility on the part of the entire health care system.

- Those in the Haitian Creole group felt that neither phrase translated easily from English to Creole.

- In the other groups, "Be your own health advocate" was preferred. Participants appreciated the connotation of "advocate" as someone who fights for him or herself and disliked the association that "champion" had with sports, which was viewed as both gendered and confusing in a health care context.

- Participants also questioned the meaning of being a "health champion" and whether that was possible in a system where–in their experience–providers rarely listen to patient concerns.

Advocate. Absolutely. I think it´s more proactive. It´s your body and your life. (Long Island)

[Champion] sounds like you´re winning something, but you shouldn´t have to be winning a basic need. (Yonkers)

And gender based, too. Champion, you know, it just sounds like a superhero type thing, where like an advocate it seems as though you´re more your normal - we´re on the same, you know, plane. I´m not gonna save you from yourself, basically. We´re here to help. So, it´s more of a communal type thing, you know, than champion. Champion seems like, "Oh, the poor pathetic, I´m gonna champion, you know, put on my cape and, you know." (Yonkers)

Additional recommendations for message content

- Participants suggested more general educational campaigns would help demystify the healthcare system. They recommended dissemination of materials on how to choose a doctor and insurance plan and information about the specifics of Medicaid benefits.

- Additional recommendations included more information to promote healthy lifestyles, such as smoking cessation strategies, healthy food access, and alternatives to medications, as well as one-page documents on common chronic diseases and how to prevent them.

- In the non-English language groups, participants reported a lack of information in the languages they speak and emphasized the importance of multilingual materials.

It is preferable that municipal authorities provide all important information using the native language of the person they send it to. If they send it to Russian people then let it be in Russian, let them send it in Japanese for Japanese people. (New York City, Russian)

There are so many different things that Medicaid provides for

you, whether it be connections or different services. And I never knew about them. For ten years I was on Medicaid, and I never knew about it until the past year or so. (Syracuse)

“I think in terms of messaging, helping people to see health-seeking behavior as pretty much akin to going to the mall or if it´s not something you wait until you´re very ill to do, but you incorporate these health- seeking behaviors and actions in your daily life. And also helping them to relate to this experience to people who they look up to, because, to this day, I still remember Michelle Obama´s campaign, "Let´s Move." (New York City)

Recommended Locations and Engagement Strategies for Educational Campaign

- Participants suggested campaigns using multiple forms of media, including:

- Ads on or in buses, in subways, and on buildings, billboards, bulletin boards, radio, and television.

- Messaging in supermarkets, schools, local newspapers, Penny Savers, community newsletters, and on social media.

- Multiple participants recommended that information be made available in–or through– pharmacies, social service providers, community events (e.g., health fairs) and doctors´ offices.

How about the patient portal? I know that´s mainly for like doctors and results or whatever, but they also give messages on there. So, if they were to put in that you went in for an annual checkup and they just mention that. (New York City)

It would be best if it is provided in the newspaper. Yes, everybody reads newspaper. That is what I was telling her. We take a look at it once a week, so the advertisements do come to notice. If it is in the papers then it would help. You can give it in the newspapers, and it can also be available at the doctor´s office. (New York City, Bangla)

Field-testing survey findings

As noted above, the surveys assessed respondents´ preferences regarding the following messages:

- Message 1: Be your own advocate! It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally.

- Message 2: Be your own health champion! Even champions have the support of a team. Tell your healthcare team what matters to you so they can help you with physical and mental health needs.

- Message 3: Be your own health champion! It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally.

Consumer message preferences

As described in detail in the appendix, two versions of the field-testing survey were developed to simplify the choices each participant was asked to make. Both versions included a single question asking preference for "Be your own health advocate" versus "Be your own health champion." Questions regarding reasons underlying message preferences, clarity of message, and potential action taken tested Message 1 against Message 2 in one version and Message 2 against Message 3 in the second version.

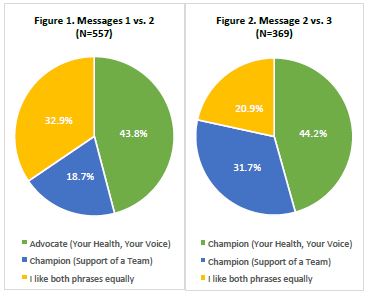

- The majority of respondents who received the Message 1 versus Message 2 survey preferred Message 1 (43.8% versus 32.9%), while those that received the Message 2 versus Message 3 survey preferred Message 3 (44.2% versus 31.7%) (See Figures 1 and 2, below).

- It is notable that the preferred messages on both versions of the survey include the text, "It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally."

Regardless of which message respondents preferred, the most frequently cited reasons for choosing the messages were:

- "The message was clear and easy to understand"

- "I relate to the message personally"

- "The message was motivating" See Appendix H for complete tables.

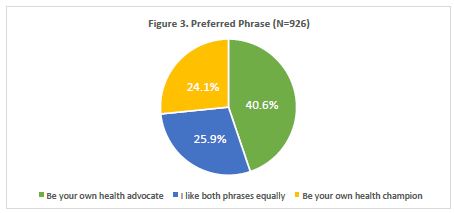

All survey respondents were asked to indicate preference between ‘Be your own health advocate´ and ‘Be your own health champion,´ independent of the full messages.

Overall, respondents preferred advocate (40.6%) over champion (24.1%), though a quarter liked them equally (25.9%).

- In most subgroup analyses (analyses that compared responses by age, location, insurance status, etc.), "Be your own health advocate" remained the preference. The most notable differences across groups were in those that liked the phrases equally. For example, older people (including older people on Medicaid) more commonly responded that they liked the phrases equally than younger people (See Appendix I for Table 8).

- Respondents on Medicaid ages 26-45 and those who live in Buffalo preferred "Be your own health champion." (See Table 9 below). Among the respondents completing the survey in languages other than English, the only statistically significant difference in preference was by age: 66.7% ages 18-25 preferred advocate while those age 26 and older preferred advocate and champion equally (See Appendix J for table 10).

| Table 9. Tagline Preference among Medicaid Members, by Age and Location (N= 413) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Location | |||||||

| 18-25 | 26-45 | 46-65 | 66+ | Albany | Buffalo NYC | Other | ||

| Be your own health advocate | 56.5% | 28.7% | 37.6% | 27.0% | 38.2% | 23.2% 36.4% | 45.0% | |

| Be your own health champion | 19.6% | 36.2% | 20.4% | 18.9% | 25.0% | 34.1% 24.0% | 30.0% | |

| Both phrases | 15.2% | 24.7% | 40.1% | 46.0% | 34.2% | 25.6% 34.6% | 22.5% | |

| None of the phrases | 8.7% | 10.3% | 1.9% | 8.1% | 2.6% | 17.1% 5.1% | 2.5% | |

| Pearson´s χ2 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||

Messages: communication and action

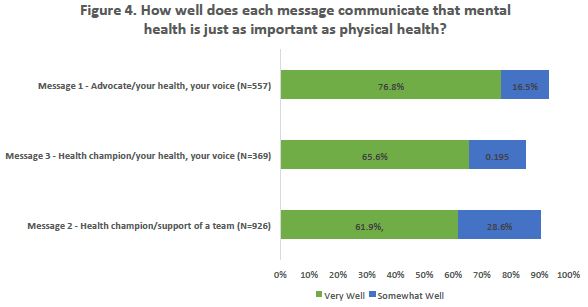

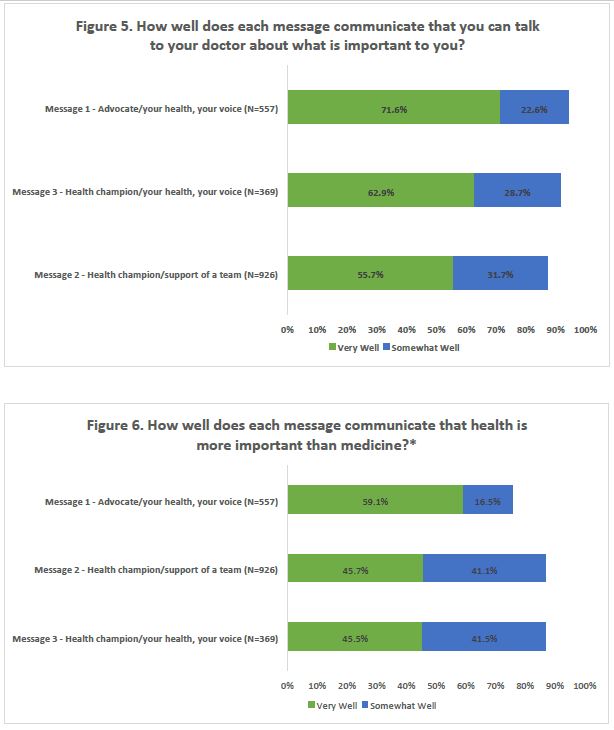

Participants were asked how well the specific messages communicated three intended ideas, as described below. Responses were on a three-point rating scale: "not well at all," "well" and "very well." Among the three messages, "Be your own health advocate" appeared to communicate the intended ideas better than the other messages.3

- 76.8% of respondents responded that "Be your own health advocate" communicated "very well" that "mental health is just as important as physical health," compared to 61.9% and 65.5% for Messages 2 and 3, respectively.

- 71.6% of respondents thought "Be your own health advocate" communicated very well that they "can talk to their doctor about what is important to you." For Messages 2 and 3 respectively, 55.7% and 62.9% of respondent felt the message communicated this very well.

- For "Be your own health advocate," 59.1% of respondents indicated the message communicated "very well" that "health is more than medicine." For messages 2 and 3, fewer than half (45.7% and 45.5%, respectively) of respondents indicated this. (See Figures 4-6 below)

Figures 4-6. Message Communication4

Overall, most respondents reported higher likelihood to take action after seeing Message 1 (advocate), than Messages 2 or 3.5 Overall, more than 6 in 10 respondents reported they were "likely" or "very likely" to take action after seeing any of the three messages [See Appendix K]. Slight differences were observed by message:

- More respondents (81.0%) who saw Message 1 said they were likely to share the message with their friend or family member than those who saw Messages 2 (66.1%) or 3 (75.1%).

- More respondents (70.2%) said they were likely to change something about the way they use healthcare after seeing Message 1 compared to Message 2 (66.1%) or Message 3 (66.2%).

Font and background color preferences

Survey respondents were asked to identify the font color, background color, and font and background color combination they liked best.

- No strong preferences emerged from the data, though a blue background was most popular both on its own, and in combination with a font color.

- Of the four font color choices–green, black, purple and red–green was the most popular by a very small margin (28.7% versus 27.2% for black, the next most popular font color).

- Of the background color options, most respondents preferred blue (39.1%).

- Preference regarding color combination was fairly even across all twelve options. However, the most popular combination–by a small margin–was blue background with black font (12.1%).

See Appendix L. for all font and background color choices and responses- including specific information about responses from Medicaid and uninsured participants as well as those who speak languages other than English.|top of section| |top of page|

V. Summary and Recommendations

The summary and recommendations are divided into two sections. The first section focuses on the educational campaign specifically, including general and specific recommendations. The second section focuses on the project in general, including lessons learned about consumer engagement and the health-related needs of low-income New Yorkers. Although most of the points below refer to information provided in the body of this report, there is also reference to information from the report appendices, as well as the more detailed focus group reports submitted previously.

Educational campaign

- Focus group participants and survey respondents preferred "Be your own health advocate" to "Be your own health champion." However, there was more variability in preference among survey respondents with some subgroups preferring the latter and many respondents, including older adults–and older adults on Medicaid–liking them equally. o There was a preference for "Be your own health champion" among respondents in Buffalo, suggesting the possibility of tailoring messages by location.

- There was a concern in the Haitian Creole focus group regarding appropriate translation of what might be somewhat abstract concepts: champion and advocate. The extent to which translation may be an issue for other languages and cultures should be explored more fully.

- Participants preferred messages with the text: "It´s your health and your voice. Sometimes life´s stresses can impact your physical health. Tell your doctor what matters to you and get the support you need to feel your best - physically and emotionally." This text also more effectively communicated the intended information. It is recommended that independent of tagline, the "It´s your health and your voice" text be used.

- Focus group participants readily described health messaging campaigns that they felt were impactful, suggesting an educational campaign around health care could be influential. They described gaps in basic health care information. Combining information, they recognize as lacking (e.g., services covered by Medicaid or how to choose a doctor) with those of interest to NYS DOH might increase effectiveness.

- Focus group participants recognized the need to advocate for themselves and reported many efforts to do so. They expressed concern that providers and systems did not respond well to these efforts and that more effort should be made to the health care side.

- Generally, people had a positive reaction to all messages and indicated that they would be likely to take action, including sharing the message or changing something about the way they use health care after seeing the messages.

- No combination of font and background color emerged as a strong preference, though the blue background as a standalone was preferred by 40% of respondents.

Consumer engagement and needs

- Participants greatly appreciated the opportunity to describe their health care experiences and provide advice to the NYS DOH regarding changes in health care and how consumers best respond to them. Continued engagement with community members is likely to be of mutual benefit.

- Many focus group participants had significant needs, but relatively few benefited from recent changes in health care; those in more rural areas of the state, in particular, reported insufficient services and few options. It would be important that messages be consistent with local realities and not suggest access to services that do not yet exist.

_________________

1. A more in-depth report on the findings from the focus groups can be found in the final focus group report to NYS DOH: Band 4 Summary Report. 1

2. These groups were held in Huntington, Long Island (in Haitian Creole); Oneonta; Riverhead, Long Island; and Yonkers. 2

3. Percentages reported are based on proportion of responses per each message 3

4. Note: *The "Not well at all" response rate not represented in the table as it accounts for 10% or less responses 4

5. Percentages reported are based on proportion of responses per each message 5

Follow Us