2005 Foodborne Disease Outbreaks in New York State

- 2005 Foodborne Disease Outbreaks in New York State (PDF, 220KB, 30pg.)

Executive Summary

Data pertaining to all foodborne disease outbreaks in New York State are collected and maintained at the Bureau of Community Environmental Health and Food Protection of the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH). The data obtained regarding the foodborne disease outbreaks that occurred in New York State in 2005 were analyzed with the following results:

- The NYSDOH reported 58 foodborne disease outbreaks in 2005. Fewer outbreaks occurred in only 3 other years since data collection began in 1980.

- In 2005, 771 individuals contracted a foodborne illness. Thirty-eight (38) people required hospitalization and one person died as a result of his illness.

- This data shows a decrease in the number of people ill, hospitalized and deceased when compared with 2004.

- Twenty (20) outbreaks were attributed to bacterial illness, making bacteria the most common cause of foodborne illness outbreaks.

- Salmonella species were responsible for 7 of the 20 bacterial outbreaks.

- The second most common cause of foodborne illness outbreaks was chemical poisoning/intoxication, which resulted in 8 outbreaks. This is a large increase when compared to 2004.

- Of these 8 outbreaks, half were a result of scombrotoxin poisoning.

- Fewer outbreaks were caused by pathogens introduced by infected workers.

- The number of outbreaks in which the implicated ingredient was a starchy food increased.

- Far fewer outbreaks implicating inadequate hot-holding, inadequate reheating and preparing foods several hours prior to service as contributing factors were reported in 2005.

- 2005 showed the highest number of outbreaks without a confirmed or suspect etiology since 1985, with nearly 40% of the outbreaks having an unknown cause.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Methods

- General Overview of 2005 Foodborne Disease Outbreaks

- Analysis of Etiology

- Agent-Specific Morbidity and Mortality Burden

- In-Year Temporal Trend

- Method of Preparation

- Significant Ingredient

- Associations between Etiologic Agent, Method of Preparation and Significant Ingredient

- Contributing Factors

- Location of Food Consumption

- Discussion

- Conclusion/Recommendations

- Case Studies of Selected 2005 Outbreaks

- References

- Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Foodborne Disease Surveillance Officers

Introduction

The New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) Foodborne Disease Surveillance System is a collaborative effort between personnel in the Bureau of Community Environmental Health and Food Protection, Regional Offices, Local Health Departments, State District Offices, Wadsworth Center, the Bureau of Communicable Disease Control, Emerging Infections Program and the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets. These groups work together to identify, investigate and mitigate the effects of the foodborne disease outbreaks occurring in New York State.

The Foodborne Disease Surveillance database contains information from all foodborne disease outbreaks reported in New York State. This database has been in use since 1980 and contains information regarding the etiology, method of preparation, significant ingredient and contributing factors identified in foodborne disease outbreak investigations.

This report summarizes the analyses of the foodborne disease outbreaks that occurred in 2005 that were reported to and investigated by the NYSDOH.

Methods

The criteria used in determining the etiology of the reported foodborne disease outbreaks in New York State in 2005 followed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) "Guidelines for Confirmation of Foodborne-Disease Outbreaks."1 The CDC defines a foodborne-disease outbreak (FBDO) as an incident in which two or more persons experience a similar illness resulting from the ingestion of a common food in the United States. Prior to 1992, three exceptions existed to this definition; botulism, marine-toxin intoxication or chemical intoxication only required one case to be considered a FBDO if the etiology was confirmed. The CDC changed the definition in 1992, requiring two or more cases to constitute an outbreak.1 Because of this, single cases occurring after 1992 were excluded from the analysis.

Criteria for assessing and interpreting the method of preparation and significant ingredient are described in the "Use of Foodborne Disease Data for HACCP Risk Assessment," Weingold, et al.2 Criteria for assessing and interpreting contributing factors are described in the "Surveillance of Foodborne Disease III. Summary and Presentation of Data on Vehicles and Contributory Factors; Their Value and Limitations," Bryan, et al.3

The following definitions of "confirmed," "suspected" and "unknown" are observed in the New York State Foodborne Disease Surveillance System:

- An outbreak is categorized as confirmed when epidemiologic evidence implicates an agent and confirmatory laboratory data are available.

- An outbreak is categorized as suspected when epidemiologic evidence and/or a food preparation review implicates an agent but no confirmatory laboratory data are available.

- The unknown category is used when epidemiologic evidence clearly associates food with the outbreak, but no laboratory data are available and the epidemiologic evidence does not clearly implicate a specific agent.

The contents of the foodborne disease surveillance database were exported to a Microsoft Excel file. This Excel file was imported into SAS v9.1 (The SAS Institute in Cary, North Carolina) and all analyses were performed using SAS v9.1. Microsoft Excel was used to create charts and tables as necessary for data reporting.

General Overview of 2005 Foodborne Disease Outbreaks

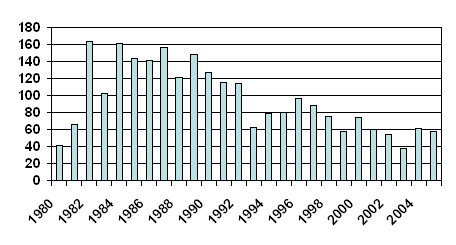

In 2005, 58 outbreaks of foodborne disease were reported by the NYSDOH. There have only been 3 years since data collection began in 1980 when fewer outbreaks were reported (Figure 1). The 2005 outbreaks consisted of 771 cases that resulted in 38 hospitalizations and one death. This is a decrease from 2004 when there were 62 reported outbreaks of foodborne disease in New York State that consisted of 1287 cases, 48 hospitalizations and two deaths. These outbreak totals do not include the single cases of intoxication with scombrotoxin that are reported and investigated. There were five cases of scombrotoxin in 2005 with no resulting hospitalizations. This was an improvement over the 2004 data in which nine cases of scombrotoxin were reported with one individual being hospitalized.

Analysis of Etiology

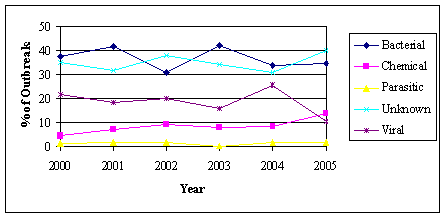

The etiology was confirmed in 27 (46.6%) of the 58 outbreaks that occurred in 2005 and a suspected etiology was documented for 8 (13.8%) of them. No known etiology was identified for the remaining 23 (39.7%) outbreaks. In the five previous years (2000 – 2004), there were 289 outbreaks. A confirmed etiology was identified for 135 (46.7%) of the outbreaks. Ninety-eight (less than 34%) of the outbreaks occurring from 2000 through 2004 had an unknown etiology.

Of the 27 outbreaks in 2005 with a confirmed etiology, 16 (59.3%) were bacterial, 8 (29.6%) were chemical, 2 (7.4%) were viral and 1 (3.7%) was parasitic. Of the 135 outbreaks that occurred from 2000 through 2004 with a confirmed etiology, 88 (65.2%) were bacterial, 14 (10.4%) were chemical, 29 (21.5%) were viral and 4 (3.0%) were parasitic.

Of the 8 outbreaks in 2005 with suspected etiologies, 4 were suspect bacterial and 4 were suspect viral. Of the 56 outbreaks that occurred between 2000 and 2004 categorized with a suspected etiology, a bacterial etiology was suspected in 19 (33.9%), viruses were suspected in 31 (55.4%) outbreaks and chemical agents were suspected in 6 (10.7%).

Figure 2 displays the contribution of each of these general classes of agents implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks since 2000.

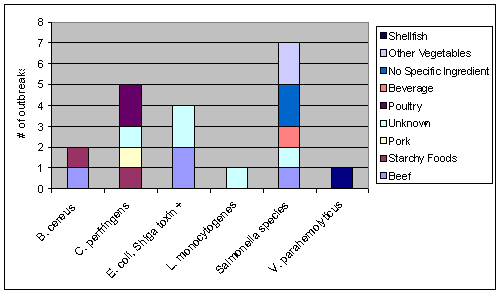

In 2005, the outbreaks with a confirmed or suspected bacterial etiology were attributed to six bacterial genera – Salmonella species, Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli, Clostridium perfringens, Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus cereus and Vibrio parahemolyticus. Outbreaks related to chemical contamination were divided among five categories – scombrotoxin intoxication, ciguatera toxin intoxication, heavy metal poisoning, consumption of poisonous mushrooms and exposure to other chemicals (calcium oxalate). Outbreaks attributed to viruses were divided among calicivirus (Norwalk virus), hepatitis A virus and rotavirus, while the lone parasitic outbreak was due to Giardia lamblia.

Table 1 compares specific agents attributed to the outbreaks that occurred in 2005 to those attributed to outbreaks that occurred between 2000 and 2004.

Agent-Specific Morbidity and Mortality Burden

Of the 423 illnesses associated with foodborne disease outbreaks that occurred in 2005 with a confirmed or suspected etiology, the highest morbidity burden was associated with Salmonella species which resulted in 117 (27.7%) illnesses. Other significant contributors to overall morbidity in 2005 were Shiga toxin producing E. coli which caused 65 illnesses (15.4%), calicivirus (Norwalk virus) which caused 63 (14.9%) illnesses and G. lamblia with 50 (11.8%) illnesses. This stands in contrast to the period between 2000 and 2004, when Salmonella species were the third leading cause of illness associated with foodborne disease outbreaks (882 of 5317 illnesses; 16.6%). Calicivirus (Norwalk virus) was the leading cause of illness associated with foodborne disease in this period, causing 1208 (22.7%) of the 5317 illnesses between 2000 and 2004. Shigella species took second place, causing 891 (16.8%) of the illnesses. It should be noted that 886 of the 891 cases associated with Shigella species over these five years occurred in one outbreak. (Table 2)

One death was associated with a foodborne disease outbreak in 2005 and Listeria monocytogenes was the confirmed etiology. There were 4 deaths associated with the outbreaks that occurred between 2000 and 2004. All occurred in separate outbreaks; one had a confirmed etiology of L. monocytogenes, one had a confirmed etiology of Hepatitis A virus and two had confirmed etiologies of Shiga toxin producing E. coli.

In-Year Temporal Trends

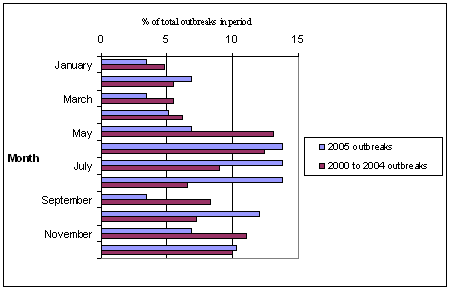

Forty-one percent (41%) of the outbreaks reported in 2005 occurred in June, July and August with 8 outbreaks reported each of the 3 months. Outbreaks peaked earlier in the five preceding years, in which the largest number of outbreaks occurred in May and steadily declined through the remainder of the summer. (Figure 3)

Salmonella species are traditionally the bacterial agent most often implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks May through August. In 2005, Salmonella species caused six (21.4%) of the 28 outbreaks that occurred May through August. From 2000 through 2004, Salmonella species were associated with 23 (19.3%) of the 119 outbreaks that occurred in the summer months. There was also an increase in the number of outbreaks with unknown etiology in the summer of 2005 (10 of 28 outbreaks; 35.7%) when compared to the previous five summers (29 of 119 outbreaks; 24.4%). These increases were accompanied by a decrease in the number of outbreaks attributed to calicivirus (Norwalk virus) in this period. One (3.6%) of the 28 outbreaks was attributed to calicivirus in 2005 and 14 (11.8%) of the 119 outbreaks were caused by calicivirus in 2000 through 2004.

In 2005, all outbreaks that occurred May through August resulted in 466 illnesses (60.4%). Of the 7172 illnesses that occurred during 2000 through 2004, 3245 (45.2%) occurred May through August.

Another peak in the number of outbreaks was noted at the end of the calendar year, typically occurring in the months of October through December. Seventeen (29.3%) of the 58 outbreaks in 2005 occurred at this time, consistent with the data for 2000 through 2004 in which 82 (28.4%) of the 289 outbreaks occurred from October through December. During these months in 2000 through 2004 there was a high number of outbreaks with unknown etiologies (37.8%) similar to 2005 when 41.2% of the outbreaks that occurred October through December had an unknown etiology. Likewise, the number of outbreaks attributed to calicivirus (Norwalk virus) October through December was similar over the years. In 2005, 2 (11.8%) of the 17 outbreaks that occurred in the last quarter and 10 (12.2%) of the 82 outbreaks in the last quarter of 2000 through 2004 were attributed to calicivirus (Norwalk virus).

Method of Preparation

The most frequently reported method of preparation was a natural toxicant present in the food that could not be destroyed or inactivated during preparation. This was reported in 6 (10.3%) of the 58 outbreaks in 2005, followed by cook/serve foods and multiple foods. Both of these were cited in 5 (8.6%) of the 58 outbreaks.

Natural toxicant was identified nearly twice as frequently in 2005 (10.3% of 2005 outbreaks) as it was from 2000 through 2004 (5.2% of the outbreaks). The number of outbreaks associated with cook/serve foods in 2005 was consistent and the five previous years, but the number of outbreaks associated with multiple foods declined in 2005. The number of outbreaks with an unknown method of preparation was consistent in 2005 and the previous five years (Table 3).

The method of preparation in 2005 was not identified in 21 (36.2%) of the outbreaks. Twelve (52.2%) of the 23 outbreaks with an unknown etiology had an unknown method of preparation, while nine (25.7%) of the 35 outbreaks with a confirmed or suspected etiology had an unknown method of preparation.

Significant Ingredient

The most frequently reported significant ingredient was starchy foods (6 of 58 outbreaks; 10.3%), followed by poultry and fin fish (5 of 58 outbreaks; 8.6% each). The number of outbreaks in which starchy foods were identified as the significant ingredient was the highest since 1990.

As with method of preparation, the number of outbreaks with unknown significant ingredients (34.5%) was similar to that seen from 2000 through 2004. However, starchy foods were identified as the significant ingredient three times more often in 2005 and food contaminated by an infected worker was identified as the significant ingredient about two and a half times less often than in the five previous years. (Table 4)

For 20 (34.5%) of the outbreaks in 2005, the significant ingredient associated with the outbreak was unknown. Twelve (52.2%) of the 23 outbreaks with an unknown etiology had an unknown significant ingredient and 8 of the 35 outbreaks with a confirmed or suspected etiology (22.9%) had an unknown significant ingredient.

Associations between Etiologic Agent, Method of Preparation and Significant Ingredient

No method of preparation was found to be significant, most likely attributable to the small number of outbreaks that were reported in 2005. The most commonly identified significant ingredient, starchy foods, was implicated in six outbreaks. These outbreaks were distributed among five methods of preparation including baked goods, cook/serve foods, salads prepared with one or more cooked ingredients, solid masses of potentially hazardous foods and other, in which the incriminated food was pork fried rice.

No etiologic agent was found to be significant, again most likely due to the small number of outbreaks reported in 2005. For example, the agent identified most often (Salmonella species) was only identified in seven of the 35 outbreaks with a confirmed or suspected etiology. Of these 7 outbreaks, the significant ingredients were beef (1 outbreak), beverage (1 outbreak), other vegetables (2 outbreaks), no significant ingredient identified (2 outbreaks) and unknown significant ingredient (1 outbreak). The term "no significant ingredient" is used when specific ingredients were identified as possible vehicles of the illness but none were statistically significant and "unknown ingredient" is used when it is unknown what food item may have caused the illness. Figures 4 through 7 illustrate the significant ingredients associated with etiologic agents in outbreaks during 2005.

Of the 21 outbreaks without a known method of preparation, 20 outbreaks had an unknown significant ingredient and one outbreak had food contaminated by an infected worker as the significant ingredient.

Contributing Factors

No contributing factors were identified during the outbreak investigations in nearly 25% of the foodborne outbreaks in 2005. Of the contributing factors that were identified, the most frequently cited were contaminated ingredients (46.4% of outbreaks with an identified contributing factor) and natural toxicant (25.0% of the outbreaks with an identified contributing factor). Both of these showed an increase over what was reported from 2000 through 2004. In 2005, the number of outbreaks for which an infected person, inadequate hot-holding, inadequate reheating and food preparation several hours before serving were identified as contributing factors showed a significant decrease when compared to 2000 through 2004. (Table 7)

Locations of Food Consumption

The two most common places of food consumption related to foodborne disease outbreaks in 2005 were restaurants (34 of 58 outbreaks; 58.6%) and the home (16; 27.6%). This was an increase over the 2000 through 2004 data in which the food was consumed in restaurants in 113 (39.1%) of the 289 outbreaks and the food was consumed in the home in 61 (21.1%) of the outbreaks.

The distribution of etiologic agents responsible for the outbreaks differed for outbreaks in which the food was consumed in a restaurant when compared to outbreaks in which the food was consumed in any other location. The etiologic agent was unknown in 15 (46.9%) of the 32 outbreaks in which food was consumed in a restaurant, compared to 8 (30.8%) of 26 outbreaks in which food was not consumed in a restaurant. All 2005 outbreaks in which the etiologic agent was identified as B. cereus (2 outbreaks), V. parahemolyticus (1 outbreak) and calicivirus (Norwalk virus) (4 outbreaks) occurred following the consumption of food in restaurants. None of the 2005 outbreaks in which the etiologic agent was identified as Shiga toxin producing E. coli (4 outbreaks), ciguatera toxin, heavy metal poisoning, mushrooms, G. lamblia, Hepatitis A virus and rotavirus (1 outbreak each) occurred following consumption of food in restaurants.

Discussion

The 58 foodborne disease outbreaks reported by the NYSDOH for 2005 contributes to the downward trend in outbreaks that began in 1992. In 2005, the average number of individuals ill in each outbreak, 13 per outbreak, was the lowest in the 26 years since the development of the current outbreak surveillance system. The one fatality in 2005 is consistent with most other years; there was one or no deaths reported annually during 16 of the 26 years of data. Only one of the 26 years reported more than four deaths due to a foodborne illness outbreak.

In the recent past, data analysis pointed to specific agents and ingredients such as Salmonella species and eggs as causing a majority of the foodborne illness outbreaks. Inspectors and investigators focused their attention on these specific risks and the number foodborne illness outbreaks associated with Salmonella and eggs declined. While four outbreaks of scombrotoxin intoxication indicate that temperature abuse of fin fish must be addressed, the variation of implicated agents, significant ingredients and methods of preparation cited in other outbreaks reported in 2005 make it difficult to specify any one area for inspectors to focus on to reduce the incidence of food borne disease. Inspectors and investigators must be vigilant against numerous factors that contribute to outbreaks in order to reduce foodborne disease outbreaks in New York State.

It is important to remember that the foodborne disease outbreaks reported here represent only a small portion of the overall morbidity burden of foodborne disease in New York State. For example, in New York State in 2005, there were seven reported outbreaks of salmonellosis with 117 cases, but overall there were 2,625 cases of salmonellosis reported in New York State in 2005, similar to numbers seen in 2004 (2,555 cases) and 2003 (2,586 cases). While some of these cases may not be foodborne or may be single cases, some may also be due to unrecognized outbreaks.

The number of outbreaks for which the etiology was unknown identifies a need for improvement. The number of outbreaks with unknown etiologies in 2005 (39.7% of outbreaks) was the highest since 1985. While it is not possible to know the agent responsible, it was observed that the increase in the number of outbreaks with an unknown etiology in 2005 (39.7% compared to 30.6% in 2004) was accompanied by a decrease in confirmed/suspected viral etiologies (10.3% compared to 25.8% in 2004).

One major limitation to the analysis of the data is that there was no way to determine where the food was prepared, only where it was consumed. Location of consumption could have an impact if food was consumed in the home but purchased in a ready-to-eat form from an establishment such as a restaurant or grocery store.

Conclusions/Recommendations

Based on the analysis of foodborne disease outbreaks in New York State in 2005 and analysis of trends from recent years, recommendations for improving both public health and the quality of the foodborne disease surveillance system are listed below.

- Reduction of scombrotoxin intoxication following temperature abuse of fin fish

Scombrotoxin intoxication remains a constant source of foodborne disease outbreaks. Although the morbidity and mortality associated with these outbreaks is typically small, these outbreaks can be prevented by the appropriate monitoring of storage temperatures for fin fish.

- Focus on classes of starchy foods

Outbreaks attributed to starchy foods increased in 2005 relative to the five previous years. These investigations did not identify a method of preparation, etiologic agent or contributing factor common to the majority of outbreaks with a significant ingredient of starchy foods. Food service establishment inspectors, foodborne disease investigators and consumers must be aware of the potential for starchy foods to be a vehicle for foodborne disease.

- Reduction of unknown etiologies

As stated previously, a large number of outbreaks occurring in 2005 had an unknown etiology. Many of these outbreaks also had unknown method of preparation and significant ingredient. It is important to ensure that biologic specimens are obtained from ill individuals and samples of implicated foods are collected during outbreak investigations.

- Sporadic Salmonella Cases

As stated previously, 117 cases of salmonellosis associated with foodborne outbreaks were reported in 2005, yet there was a total of 2625 cases reported in the State. While some of these cases may be a single sporadic cases not associated with outbreaks, more likely, this disparity is a result of underreporting and unidentified outbreaks. Techniques such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and the collaboration of state and federal laboratories through PulseNet, the National Molecular Subtyping Network for Foodborne Disease Surveillance at CDC, which New York State is a part of, provide the opportunity to link cases occurring in different locations and identify outbreaks that would otherwise go unrecognized.

- Ill food worker

In most of the outbreaks with an unknown etiology, evidence supports a viral agent. These outbreaks, coupled with the fact that infected worker was identified as a significant ingredient 2.5 times less than in the past support the need for educating the food worker about the importance in using a proper barrier when handling ready to eat foods. This may also indicate a need to remind the outbreak investigators of the importance of identifying ill food workers and citing them as a contributing factor if necessary.

Case Studies of Selected 2005 Outbreaks

The foodborne disease outbreaks that occurred in New York State in 2005 were varied. Several narratives are presented below to illustrate the challenges faced and successes achieved by foodborne disease surveillance staff during the investigations.

- Giardia lamblia outbreak in a residential private school/children's camp – Essex County

In August, 50 individuals became ill with giardiasis at a children's camp held at private residential school. The outbreak occurred following a party at the end of the camp season that was held concurrently with several back-to-school parties. The camp and the school harvested vegetables, fruits and berries from a garden on school property for the parties. Goats, also housed on school grounds, were not kept from entering the garden. Other animals present at the school included horses, llamas, chickens, pigs and sheep. School and camp residents were directly exposed to the animals and their manure and one goat tested positive for G. lamblia. Not all produce harvested from the garden was washed, and the produce that was washed was washed with water from a nearby brook. Hypotheses about the source of the outbreak included the goats, the other animals, the brook and the garden irrigation. The definitive source of outbreak was not determined.

- Heavy metal poisoning at a private residence – Ontario County

In July, six individuals became ill with copper poisoning at a private home within two hours of ingesting iced tea. Family members and the landscaper experienced symptoms that included nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Pre-sweetened lemon flavored iced tea mix was prepared and stored for at least 18 hours in a copper based pitcher that had an eroded silver-plated surface. The pitcher had also been polished with tarnish remover three weeks earlier.

- Enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7 – Saratoga County

In October, a mother, daughter and friend of the daughter became ill after consuming cooked pre-formed hamburger patties. The three individuals experienced diarrhea, abdominal cramps and bloody stools. Stool specimens were positive for E. coli O157:H7, but no one was hospitalized. Leftover ground beef patties were available at the residence in which they were prepared. These patties were tested and were positive for E. coli O157:H7. The bacterial isolates from the ill individuals and the hamburger patties were analyzed with pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and identified as matching strains. This led to the identification of a multi-state outbreak that resulted in a nationwide voluntary recall of nearly 100,000 pounds of hamburger patties.

- Intoxication following ingestion of poisonous mushrooms – Westchester County

In October, four individuals became ill after consuming wild mushrooms. The family picked the mushrooms along the highway in Albany County and prepared and consumed them at their home in Westchester County. The mushrooms were Omphalotus olearius (Jack o' Lantern mushrooms), a poisonous mushroom similar in appearance to edible chanterelle mushrooms. All individuals who consumed the mushrooms experienced vomiting and abdominal cramps within six hours. Two of the individuals were hospitalized, and the illness lasted three days.

- Salmonellosis due to sliced tomatoes – Erie, Genesee, Livingston, Monroe and Oneida Counties

In July, seven individuals in four counties (Genesee, Livingston, Monroe and Oneida) became ill with salmonellosis after consuming sliced tomatoes obtained at restaurants and grocery stores. Individuals who became ill reported diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, cramps, vomiting and fever. The agent was isolated and, using (PFGE), was identified as Salmonella Newport, the third most common Salmonella serotype. This particular strain of S. Newport was a PFGE match to an outbreak that occurred in 2002 at a pizzeria in Erie County. PulseNet, the National Molecular Subtyping Network for Foodborne Disease Surveillance at CDC, cited this strain as causing a multi-state outbreak. The NYSDOH Wadsworth Center Laboratories participate in PulseNet. Currently, the Bureau of Community Environmental Health and Food Protection and foodborne disease personnel in several other states are collecting data from restaurants regarding their tomato handling practices.

- Chemical (calcium oxalate) poisoning due to undercooked taro root chips – Putnam County

In December, two individuals reported sensations of tingling, burning and stinging in their mouth after consuming taro root chips. Taro root contains calcium oxalate, the agent responsible for the symptoms, but it is rendered harmless when properly prepared. The taro root chips were undercooked, and an unsafe level of calcium oxalate was present in the chips.

- Intoxication due to ciguatera toxin – Bronx County

In May, four individuals experienced itching, tingling, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, cramps and diarrhea approximately 15 minutes after consuming barracuda fish that had been fried and then stewed. One ill individual was hospitalized in intensive care for several days. The cooked fish and raw barracuda obtained from a local market were tested by the FDA and high levels of ciguatera toxin, a heat-stable toxin, were found in the samples. This outbreak differs from the marine-toxin intoxications typically seen in New York State (intoxication with scombrotoxin) in that scombrotoxin formation can be prevented by appropriate time/temperature controls of fin fish. Ciguatera toxin is a toxin that is produced by naturally occurring algae called dinoflaggelates that accumulate in tropical marine fish, including barracuda, grouper, snapper, jack, mackerel and triggerfish.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Guidelines for Confirmation of Foodborne-Disease Outbreaks," MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 49(SS01) March 17, 2000, pp. 54-62.

- Weingold SE, Guzewich JJ, Fudula JK, "Use of Foodborne Disease Data for HACCP Risk Assessment," Journal of Food Protection, Vol. 57, No. 9, 1994, pp. 820-30.

- Bryan FL, Guzewich JJ, Todd ECD, "Surveillance of Foodborne Disease III. Summary and Presentation of Data on Vehicles and Contributory Factors; Their Value and Limitations," Journal of Food Protection, 1997, Vol. 60, No. 6, pp. 701-14.

Tables and Figures

Figure 1. Chart of reported foodborne disease outbreaks in New York State, 1980 – 2005. Outbreaks reported before 1992 include investigation of single case outbreaks (e.g., single cases of scombrotoxin intoxication), which accounted for 60 outbreaks in this period.

Figure 2. Chart of general etiologic agent classes implicated for reported foodborne disease outbreaks in New York State, 2000 – 2005. .

Table 1. Etiology of foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005, compared to outbreaks between 2000 and 2004.

| Agent | 2005 | 2000 to 2004 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %* | %** | N | %* | %** | ||

| Outbreaks with confirmed etiology 2005: N=27 2000 to 2004: N=135 |

Bacterial – Campylobacter species Bacterial - C. perfringens Bacterial - E. coli: Shiga Toxin Negative Bacterial - E. coli: Shiga Toxin Positive Bacterial - L. monocytogenes Bacterial - Salmonella species Bacterial - Shigella species Bacterial - S. aureus Bacterial - V. cholera Bacterial - V. parahemolyticus Bacterial - Y. enterocolitica |

*** 2 *** 4 3 7 *** *** *** *** *** |

*** 12.5 *** 25.0 18.8 43.8 *** *** *** *** *** |

*** 3.4 *** 6.9 5.2 12.1 *** *** *** *** *** |

5 10 1 12 3 45 2 6 1 2 1 |

5.7 11.4 1.1 13.6 3.4 51.1 2.3 6.8 1.1 2.3 1.1 |

1.7 3.5 0.3 4.2 1.0 15.6 0.7 2.1 0.3 0.7 0.3 |

| Chemical - Allergen Chemical - Ciguatera Toxin Chemical - Heavy Metal Chemical - Mushrooms Chemical - Other Chemical Chemical - Scombrotoxin |

*** 1 1 1 1 4 |

*** 12.5 12.5 12.5 12.5 50.0 |

*** 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.7 6.9 |

1 *** *** *** 3 10 |

7.1 *** *** *** 21.4 71.4 |

0.3 *** *** *** 1.0 3.5 |

|

| Viral - Calicivirus Viral - Hepatitis A virus |

1 1 |

50.0 50.0 |

1.7 1.7 |

26 3 |

89.7 10.3 |

9.0 1.0 |

|

| Parasitic - G. lamblia Parasitic - C. cayatenensis |

1 *** |

100.0 *** |

1.7 *** |

2 2 |

50.0 50.0 |

0.7 0.7 |

|

| Outbreaks with suspected etiology 2005: N=8 2000 to 2004: N=56 |

Bacterial - B. cereus Bacterial - C. perfringens Bacterial - S. aureus Bacterial - V. parahemolyticus |

2 1 *** 1 |

50.0 25.0 *** 25.0 |

3.4 1.7 *** 1.7 |

6 11 2 *** |

31.6 57.9 10.5 *** |

2.1 3.8 0.7 *** |

| Viral - Calicivirus Viral - Gastrointestinal virus Viral - Rotavirus |

3 *** 1 |

75.0 *** 25.0 |

5.2 *** 1.7 |

7 24 *** |

22.6 77.4 *** |

2.4 8.3 *** |

|

| Chemical - Scombrotoxin Chemical - Other Chemical |

*** *** |

*** *** |

*** *** |

5 1 |

83.3 16.7 |

1.7 0.3 |

|

| Outbreaks with unknown etiology | Unknown | 23 | 100.0 | 39.7 | 98 | 100.0 | 33.9 |

|

* - % of outbreaks in confirmation and general agent category (e.g., Confirmed/Bacterial, Confirmed/Chemical, Suspected Bacterial) |

|||||||

Table 2. Morbidity burden of agents implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005, compared to 2000 through 2004.

| 2005 | 2000 to 2004 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # ill | %* | %** | # ill | %* | %** | ||

| Bacterial | B. cereus Campylobacter species C. perfringens E. coli: Shiga toxin - E. coli: Shiga toxin + L. monocytogenes Salmonella species Shigella species S. aureus V. cholera V. parahemolyticus Y. enterocolitica |

19 *** 29 *** 65 13 117 *** *** *** 2 *** |

2.5 *** 3.8 *** 8.4 1.7 15.2 *** *** *** 0.3 *** |

4.5 *** 6.9 *** 15.4 3.1 27.7 *** *** *** 0.5 *** |

37 87 580 28 325 41 882 891 277 2 58 4 |

0.5 1.2 8.1 0.4 4.5 0.6 12.3 12.4 3.9 0.0 0.8 0.1 |

0.7 1.6 10.9 0.5 6.1 0.8 16.6 16.8 5.2 0.0 1.1 0.1 |

| Chemical | Allergen Ciguatera toxin Heavy metal Mushrooms Other Chemical Scombrotoxin |

*** 4 6 4 2 10 |

*** 0.5 0.8 0.5 0.3 1.3 |

*** 0.9 1.4 0.9 0.5 2.4 |

15 *** *** *** 34 73 |

0.2 *** *** *** 0.5 1.0 |

0.3 *** *** *** 0.6 1.4 |

| Parasitic | C. cayatenensis G. lamblia |

*** 50 |

*** 6.5 |

*** 11.8 |

17 102 |

0.2 1.4 |

0.3 1.9 |

| Viral | Calicivirus/Norwalk virus Gastrointestinal virus Hepatitis A virus Rotavirus |

63 *** 9 30 |

8.2 *** 1.2 3.9 |

14.9 *** 2.1 7.1 |

1208 629 27 *** |

16.8 8.8 0.4 *** |

22.7 11.8 0.5 *** |

| Unknown | Unknown | 348 | 45.1 | 1855 | 25.9 | ||

|

* - % of all ill (including those from outbreaks with unknown etiology) |

|||||||

Figure 3. Month-by-month trend of outbreaks in 2005, compared to outbreaks occurring between 2000 and 2004.

Table 3. Method of preparation implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005, compared to outbreaks between 2000 and 2004.

| Method of preparation | 2005 | 2000 to 2004 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %* | %** | N | %* | %** | |

| Unknown | 21 | 36.2 | N/A | 102 | 35.3 | N/A |

| Natural toxicant | 6 | 10.3 | 16.2 | 15 | 5.2 | 8.0 |

| Cook/serve foods | 5 | 8.6 | 13.5 | 23 | 8.0 | 12.3 |

| Multiple foods | 5 | 8.6 | 13.5 | 38 | 13.1 | 20.3 |

| Foods eaten raw or lightly cooked | 4 | 6.9 | 10.8 | 7 | 2.4 | 3.7 |

| Salads with raw ingredients | 3 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 4 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Solid masses of potentially hazardous foods | 3 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 12 | 4.2 | 6.4 |

| Beverages | 2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 8 | 2.8 | 4.3 |

| Roasted meat/poultry | 2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 15 | 5.2 | 8.0 |

| Salads prepared with one or more cooked ingredients | 2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 11 | 3.8 | 5.9 |

| Baked goods | 1 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 7 | 2.4 | 3.7 |

| Commercially processed foods | 1 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 13 | 4.5 | 7.0 |

| Liquid/semi-solid mixtures of potentially hazardous foods | 1 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 12 | 4.2 | 6.4 |

| Other | 1 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 4 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Sandwiches | 1 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 16 | 5.5 | 8.6 |

| Chemical contamination | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

|

* - % of total outbreaks (2005: N = 58; 2000 to 2004: N = 289) |

||||||

Table 4. Significant ingredient implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005, compared to outbreaks between 2000 and 2004.

| Significant ingredient | 2005 | 2000 to 2004 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %* | %** | N | %* | %** | |

| Unknown | 20 | 34.5 | N/A | 102 | 35.3 | N/A |

| Starchy foods | 6 | 10.3 | 16.2 | 9 | 3.1 | 4.8 |

| Fin fish | 5 | 8.6 | 13.5 | 16 | 5.5 | 8.6 |

| Poultry | 5 | 8.6 | 13.5 | 19 | 6.6 | 10.2 |

| Beef | 4 | 6.9 | 10.8 | 24 | 8.3 | 12.8 |

| No specific ingredient | 4 | 6.9 | 10.8 | 46 | 15.9 | 24.6 |

| Introduced by infected worker | 3 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 38 | 13.1 | 20.3 |

| Other vegetables | 3 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 3 | 1.0 | 1.6 |

| Beverage | 2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Green leafy vegetables | 2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 5 | 1.7 | 2.7 |

| Shellfish | 2 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 6 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| Pork | 1 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Dairy | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Eggs | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Fruits | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.0 | 1.6 |

| Other seafood | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.0 | 1.6 |

| Other vehicle | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.7 | 2.7 |

|

* - % of total outbreaks (2005: N = 58; 2000 to 2004: N = 289) |

||||||

Figure 4. Significant ingredients associated with bacterial agents implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005.

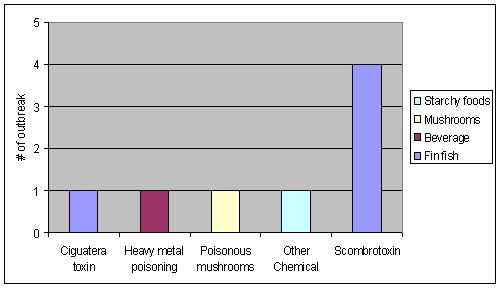

Figure 5. Significant ingredients associated with chemical agents implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005.

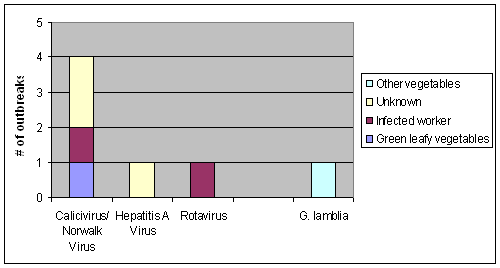

Figure 6. Significant ingredients associated with viral and parasitic agents implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005.

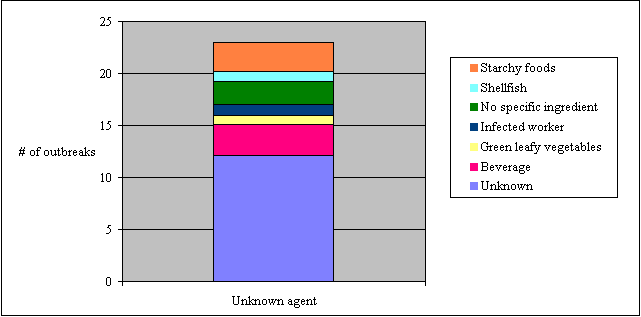

Figure 7. Significant ingredients associated with unknown agents implicated in foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005.

Table 7. Contributing factors identified in foodborne disease outbreaks, New York State, 2005, compared to outbreaks between 2000 and 2004.

| Contributing factor | 2005 | 2000 to 2004 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %* | %** | N | %* | %** | |

| Unknown | 30 | 51.7 | N/A | 156 | 54.0 | N/A |

| Contaminated ingredients | 13 | 22.4 | 46.4 | 22 | 7.6 | 16.5 |

| Natural toxicant | 7 | 12.1 | 25.0 | 15 | 5.2 | 11.3 |

| Consumption of raw/lightly heated foods of animal origin | 5 | 8.6 | 17.9 | 8 | 2.8 | 6.0 |

| Infected person | 4 | 6.9 | 14.3 | 40 | 13.8 | 30.1 |

| Inadequate refrigeration | 3 | 5.2 | 10.7 | 20 | 6.9 | 15.0 |

| Inadequate cooking | 3 | 5.2 | 10.7 | 12 | 4.2 | 9.0 |

| Improper cooling | 3 | 5.2 | 10.7 | 14 | 4.8 | 10.5 |

| Hand contact with implicated food | 3 | 5.2 | 10.7 | 17 | 5.9 | 12.8 |

| Unclean equipment | 2 | 3.4 | 7.1 | 4 | 1.4 | 3.0 |

| Inadequate hot-holding | 1 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 24 | 8.3 | 18.0 |

| Inadequate reheating | 1 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 14 | 4.8 | 10.5 |

| Unapproved sourced | 1 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 2 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| Toxic container | 1 | 1.7 | 3.6 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Food preparation several hours before serving | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18 | 6.2 | 13.5 |

| Anaerobic packaging | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Cross-contamination | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9 | 3.1 | 6.8 |

| Poor dry storage | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Added poisonous chemicals | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 1.5 |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.0 | 2.3 |

|

* - % of total outbreaks (2005: N = 58; 2000 to 2004: N = 289) |

||||||

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to lab staff employed at Local Health Departments and private labs, the New York State Department of Health Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health Bureau of Communicable Disease Control, New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, United States Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and health and agriculture agencies in surrounding states.

New York State Foodborne Disease Surveillance Officers

County, City, and District Office Foodborne Disease Surveillance Officers are gratefully acknowledged for their contributions to this report.

| County Health Department | Foodborne Disease Surveillance Officer |

|---|---|

| Albany | Marcia Lenehan |

| Allegany | Dean Scholes |

| Broome | Mark Mancini |

| Cattaraugus | Eric Wohlers |

| Cayuga | Scott King |

| Chautauqua | Gilbert House |

| Chemung | Patty Hall |

| Chenango | Rena Doing |

| Clinton | Jim Cayea |

| Columbia | Tara Hettescheimer |

| Cortland | Audrey Lewis |

| Dutchess | Spencer Marks |

| Erie | Mark Kowalski |

| Genesee | Randy Garney |

| Livingston | Mary Margaret Stallone |

| Madison | Mike Murawski |

| Monroe | John Campana |

| Nassau | Ilana Greenblatt |

| Niagara | Fabian Rosati |

| Oneida | Sue Batson |

| Onondaga | Lauri Blasi |

| Orange | Dave Score |

| Orleans | Wayne Dickinson |

| Oswego | Natalie Roy |

| Putnam | Rick Curano |

| Rensselaer | Mary Albert |

| Rockland | Jeannie Longo |

| Schenectady | Andrew Suflita |

| Schoharie | Janice Herrick |

| Seneca | Sara Brown Ryan |

| Suffolk | Bruce Williamson |

| Tioga | David Rolls |

| Tompkins | Carol Chase, Rick Ewald |

| Ulster | Denise Woodvine |

| Westchester | Gabe Sganga |

| Wyoming | Steve Perkins |

| City Health Department | Foodborne Disease Surveillance Officer |

| New York City | Faina Stavinsky |

| District and Regional Offices | Foodborne Disease Surveillance Officer |

| Western Region | Jeffery Booth, Anita Bonamici |

| Canton | Genevieve McLaughlin |

| Capital Region | Mara Holcomb, Kristen Sayers |

| Geneva | Jim Hale |

| Glens Falls | Melissa Brewer |

| Herkimer | John Manzer |

| Hornell | Leonard Arias |

| Metropolitan Region | Judyth Niconienko |

| Monticello | Mike Duffy |

| Oneonta | Bruce VonHoltz |

| Saranac Lake | Jules Callaghan |

| Central Region | Tom Okoniewski, Maggie Deitrich |

| Watertown | Laurie Sheltra |

| Bureau of Community Environmental Health and Food Protection | |

|---|---|

| Director | Michael Cambridge |

| Assistant Director | Doug Sackett |

| Section Chief, Food Protection | Barbara Gerzonich |

| Foodborne Outbreak Coordinators | David Nicholas Darby Greco Ed Carloni Amy Mears Kendell Dunham Sarah Davis Robert Bednarczyk |

This publication was supported by Grant/Cooperative Agreement Number EH 000086 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.